Labor shortages and workforce challenges

These Are The 3 Essential Talent Traits For The Next Decade

By David Maya and Tim Xu

The talent model that has ruled over large companies for decades is losing relevance in a rapidly changing global economy. Organizations that lean into this transition will have an advantage over those that don’t.

Since at least the early 1990s, free trade and open markets allowed companies to move people and resources across borders with increasing ease. The growing complexity of multinational operations and, for some industries, higher regulatory burdens required workers with ever-deeper levels of expertise.

But that has been changing over the past few years as war, political unrest, and a rising tide of economic nationalism make business conditions more challenging around the world. Some prominent thinkers believe this is just the beginning of a long period of global economic instability marked by inflation, domestic political strife, international conflict, worsening climate conditions, and disruptive technologies led by artificial intelligence. “Let’s consider the possibility that the 2020s could actually be worse than the 1970s,” economic historian Niall Ferguson said last year. The historian and economist Neil Howe predicts these clashing macro forces will play out over the next 10 years.

In such an environment, hyperspecialized organizations full of individual “role players” who have perfected their specialty but are less reliable in other areas could find themselves struggling to respond to changes in business conditions.

Welcome to the era of the “athlete.” In the years ahead, companies will prize workers with all-around strengths and a high baseline proficiency across most areas. That’s not to say specialists won’t still be crucial elements of companies’ overall talent strategies. Rather, the organizations with the right mix of athletes and role players will be best able to navigate the changes ahead.

Emerging talent dynamics for the coming decade

Decades of cognitive research has shown that deep expertise works through pattern recognition. Chess masters, for example, have near-instant recognition of more than 50,000 patterns they draw on for decision-making. In a stable environment like a chess match, role players excel: they leverage pattern recognition to make fast, accurate decisions. But when the rules change, role players can find themselves stuck or, worse, making wrong decisions by applying old solutions to new problems.

Athletes, on the other hand, quickly recognize when the rules have changed and how the team can respond. They still draw from a library of past patterns and experience to guide future decisions, but their pattern set is significantly broader.

Balanced teams with a mix of athletes and role players are a sight to see. They tend to be fluid, well integrated, and innovative, discovering systematic edges that can lead to long periods of success.

In our consulting work for major global corporations, we are seeing three talent attributes that will be particularly important in the years ahead: broad perception, generalizable expertise, and adaptability.

Broad perception for future talent

Role players with narrow scopes don’t always recognize changes quickly enough to help the team adjust quickly. Worse, they are more likely to be overconfident, believing in their intuition derived from deep expertise even when conditions don’t suit them. Athletes, on the other hand, have broad perception that allows them to see the whole playing field as it changes. They can quickly understand how disruptions threaten previously held assumptions, and then work with the experts to develop necessary adjustments.

One major US airline has built its talent model around finding and nurturing broad perception. It has focused on acquiring top young talent from both undergraduate and MBA programs, offering rotational programs that satisfy curiosity, build skillsets, and put their broad perception to work. One of the early fruits of this effort has been the development of industry-leading enterprise analytics.

Those analytics were a huge help during a particularly rough stretch recently. Every day in the United States, roughly 25,000 commercial flights need equipment, people, fuel, and cargo to be in precisely the right place at the right time in order to take off on schedule. But last year, amid difficult weather patterns, unusually strong travel demand, and severe labor shortages, US airlines posted their worst on-time performance since 2014. Customer complaints more than tripled in 2022 compared with 2019.

But the airline has survived and, by some metrics, even thrived during the turbulence. The main way it gauges consumer satisfaction is the Net Promoter Score (NPS), a measure of the likelihood of a customer recommending the company to others. A decade ago the airline set out to increase its NPS over time from less than 20% to at least 50%. Not only did it achieve that goal in 2019 — it managed to soar even higher in 2022 despite the industry’s many challenges.

Expanding skills for versatile expertise

Seeing opportunities, risks, and connections will get workers only so far. They also need the ability to engage with others across many different functions, connecting the dots across the organization to make a real impact.

For athletes, their main expertise is in reasoning, problem solving, learning, and recombining knowledge. In essence, they are experts at becoming experts — and are especially useful in unstable and changing environments. In his 2019 book “Range,” David Epstein cited research from a doctoral thesis showing that the main contributor to the development of generalized expertise is “the early development of expertise in multiple domains.”

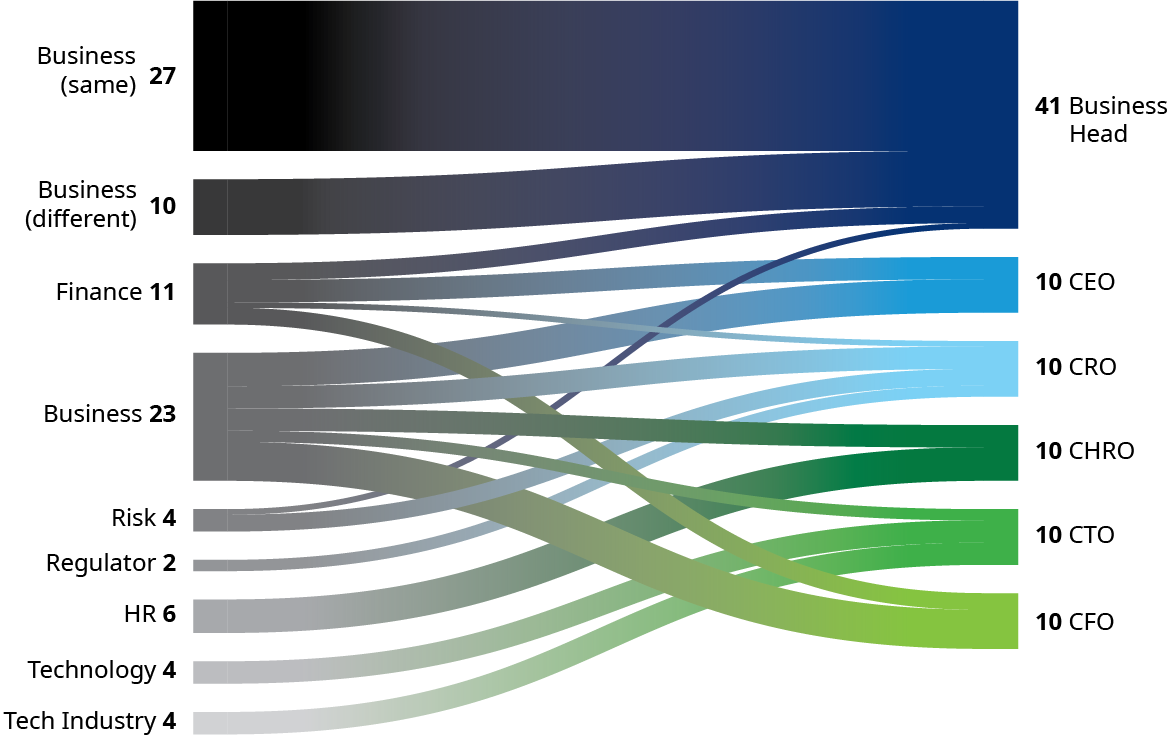

The financial services industry highlights the difference between general and specific expertise. Since the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008, many key functions at financial institutions have grown significantly and become much more specialized. Among the top 10 US banks, for example, 80% of current business heads and CEOs have no formal experience in another function.

Exhibit 1: Background of key Business and Functional executives at top 10 US Banks

Source: Oliver Wyman analysis

of Business Heads and CEOs have only ever had Business roles

Business Heads have only worked in their Business line

Chief Risk Officers (CROs) only have Risk-related backgrounds

Chief Technology Officers (CTOs) only have Technology-related experience

example of cross-functional experience (e.g., both Finance and Risk experience)

But one financial information and technology firm is bucking this trend and reaping the rewards. After facing extreme pressure during the GFC that threatened its long-term future, the firm deliberately sought more generalizable expertise. First, it brought in a new CEO who had limited experience in its businesses but was well-regarded for his leadership and stakeholder management skills. The CEO, in turn, filled his executive management team with similar athletes: a CFO who led transformations in the food and beverage industry, a technology chief experienced in banking and payments, the CEO of a key and troubled division who had been an effective and strategic human resources executive.

These athletes have leveraged their generalized expertise to drive a significant turnaround, quickly addressing core challenges, capitalizing on favorable market trends and more than doubling revenue. This team of athletes (alongside the specialists) has achieved nearly an eightfold increase in the company’s share price in the last 10 years, more than triple the S&P 500’s return over the same period.

Embracing adaptability in a changing world

Studies show that leaders with more varied backgrounds tend to marshal more innovation. That’s because broad experiences help leaders generate systematic, cross-cutting ideas to continuously adapt to a changing environment.

Retailing is an industry where people with different backgrounds can help achieve larger goals. The dot-com revolution forced companies to hire directly from Silicon Valley in order to bolt-on digital capabilities. Yet brick-and-mortar remains a huge part of retail sales, growing from $4.1 trillion in 2012 to nearly $6.1 trillion in 2022.

With that level of growth, it is easier to continue letting specialists be specialists. It’s difficult to balance the needs of older customers with, say, Generation Z, which relies heavily on social media and demands authenticity. Many retailers have therefore stuck with role playing specialists, deepening the lines between homegrown brick-and-mortar experts and imported e-commerce and digital marketing experts, or between tenured leaders and newer hires with only headquarters experience.

But one of the fastest growing retailers of the past decade is turning that model on its head. It is one of few major US grocers that competes for top undergraduate talent with technology and financial firms — including on compensation. It then systematically exposes these young athletes-to-be to a broad range of experiences and skills before placing them in leadership roles. Over the years this has created, reinforced, and sustained a culture of adaptability, producing leaders who understand all the moving pieces and can react effectively and quickly as trends change.

This groundbreaking approach to talent acquisition by the grocer reflects a paradigm shift in the retail landscape. Unlike traditional models, this retailer doesn't merely hire employees; it invests in cultivating leaders. By actively vying for top talent against tech and financial giants, the grocer signals a departure from industry norms, recognizing the importance of diverse skill sets. The intentional exposure of recruits to a wide array of experiences goes beyond job roles, fostering a culture of adaptability and resilience.

This grocer is now seeing the payoff: It is rapidly penetrating the heavily saturated US grocery market, taking advantage of changing customer preferences and an unpredictable business environment to vault into the top five.

Initiating the journey in talent transformation

The organizations that will thrive in the future will identify, attract, and train athletes, while making the organizational changes necessary for them to thrive alongside specialists.

“Big bang” changes will likely be too disruptive to work smoothly, but organizations can start with smaller steps. They can champion and systematize internal mobility across functions, identify and promote the athletes they already have, and evaluate recruiting and compensation strategies to attract more of this kind of talent.

These steps alone won’t turn organizations into thriving teams with athletes overnight. But taken together, such actions can increase resilience, innovation, and agility in the face of a shifting environment and growing uncertainty.