Renewable energy is gaining ground across the globe as countries seek to reduce their CO2 emissions. In 2023, more than 30% of the world’s energy came from renewable sources, the first time that threshold has been broken.

As part of its contribution toward achieving net zero, Indonesia has set a target to increase its share of renewables to 23% of the national energy mix by 2025. By 2022, however, the installed capacity for renewables was only 12.3% according to Climate Transparency — falling far short of its goal.

Part of the reason for this lies in the government’s reliance on private investment to build renewable infrastructure. At 6.25%, Indonesia’s interest rate is higher than most developed markets, and is characterized by relatively high credit risk and banking capital requirements, which in turn increases the cost of financing. In many markets, that risk is reduced through guaranteed offtake agreements, but because Indonesia’s market is regulated, the potential impairment cost is high. Added to this, Indonesia’s National Electricity Plan sets out rules only for its power sector development, and not for renewable energy. There is a Renewable Energy Bill in the pipeline, but the bill has yet to be ratified. Without clear guidelines, investors remain cautious.

Additionally, PLN, the state power utility, has worked hard to ensure electrification to all parts of Indonesia, and many of its coal-fired assets are relatively young. While PLN is responsible for implementing emissions reductions, it must also consider the implications of adding renewables to a fully functioning grid, and at the same time still ensuring a reliable energy supply. This is further complicated as neither the grid nor storage infrastructure is ready for significantly more renewable capacity to come online.

Despite these challenges, Indonesia’s government is implementing policies aimed at attracting investors, and the country has enormous potential to increase its mix of renewables through its abundant sources of solar and wind energy.

Understanding the true cost of renewable energy

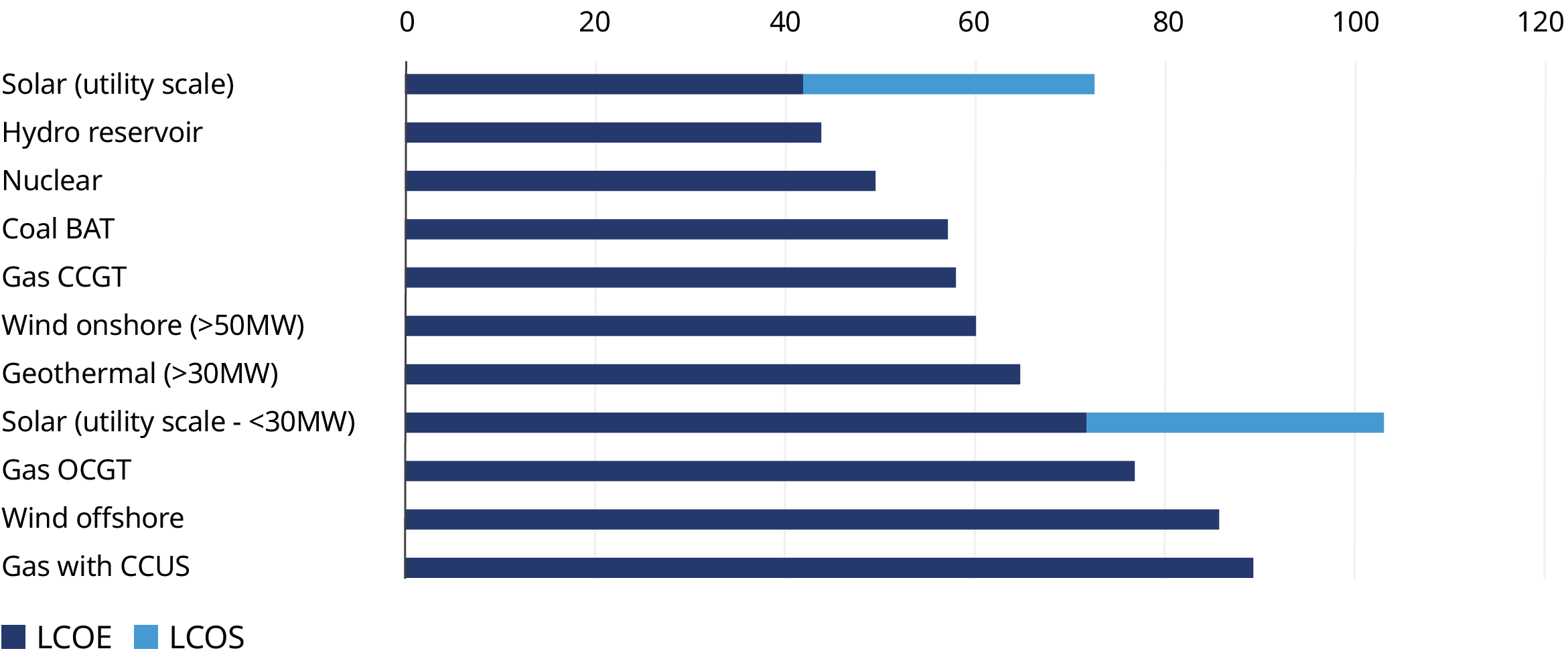

In theory, renewable energy is cheaper to produce than fossil fuels, but the way total energy costs are calculated is complex and involves an understanding of upfront investment, operating costs, and payment mechanisms. When it comes to renewables, nearly all the costs are upfront, compared to conventional power facilities, which incur continuous costs through an ongoing need for fuel. But the energy industry measures the cost of different sources of power through levelized cost — the total cost of producing energy over an asset’s lifetime, divided by the total energy it will produce in that lifetime.

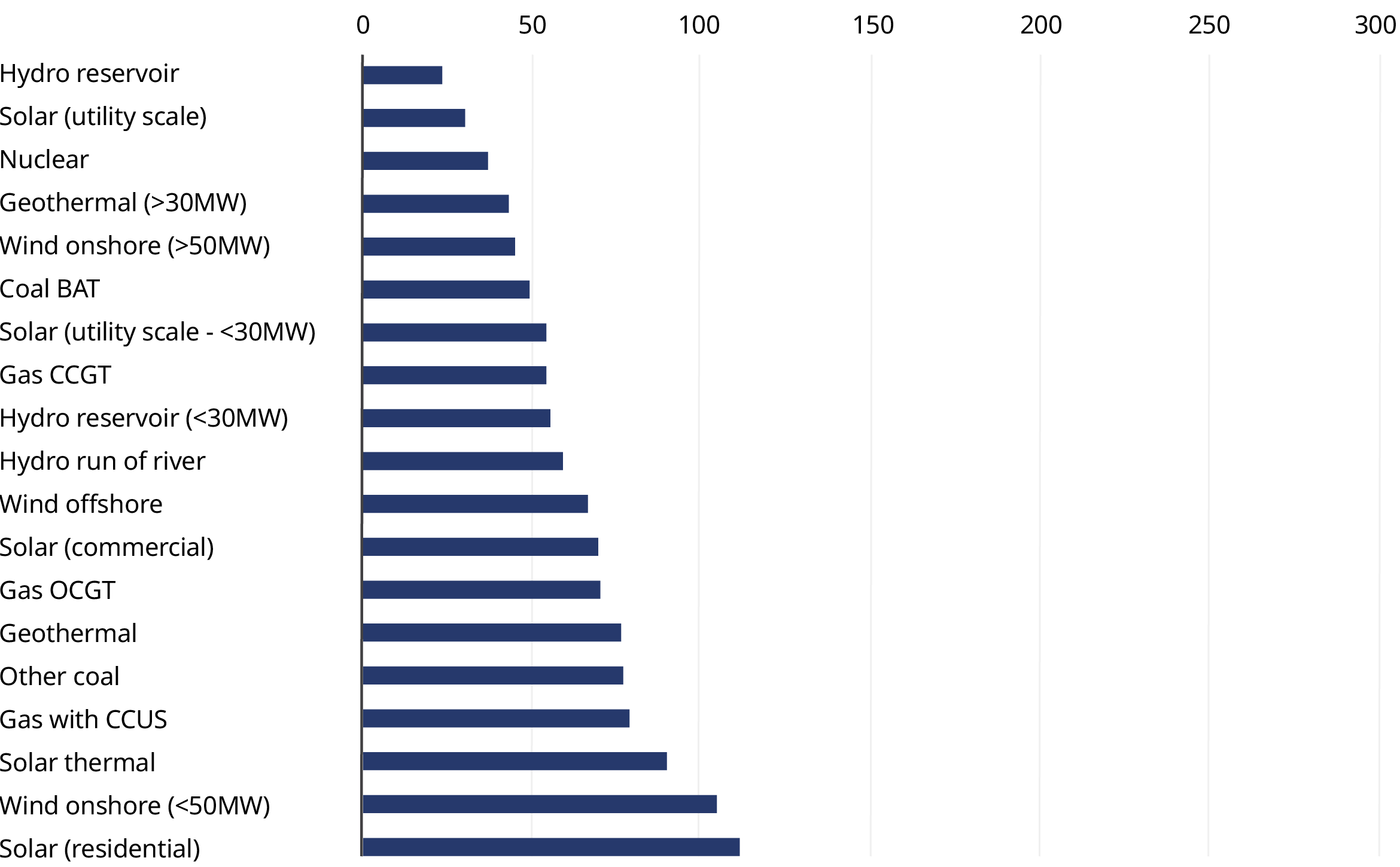

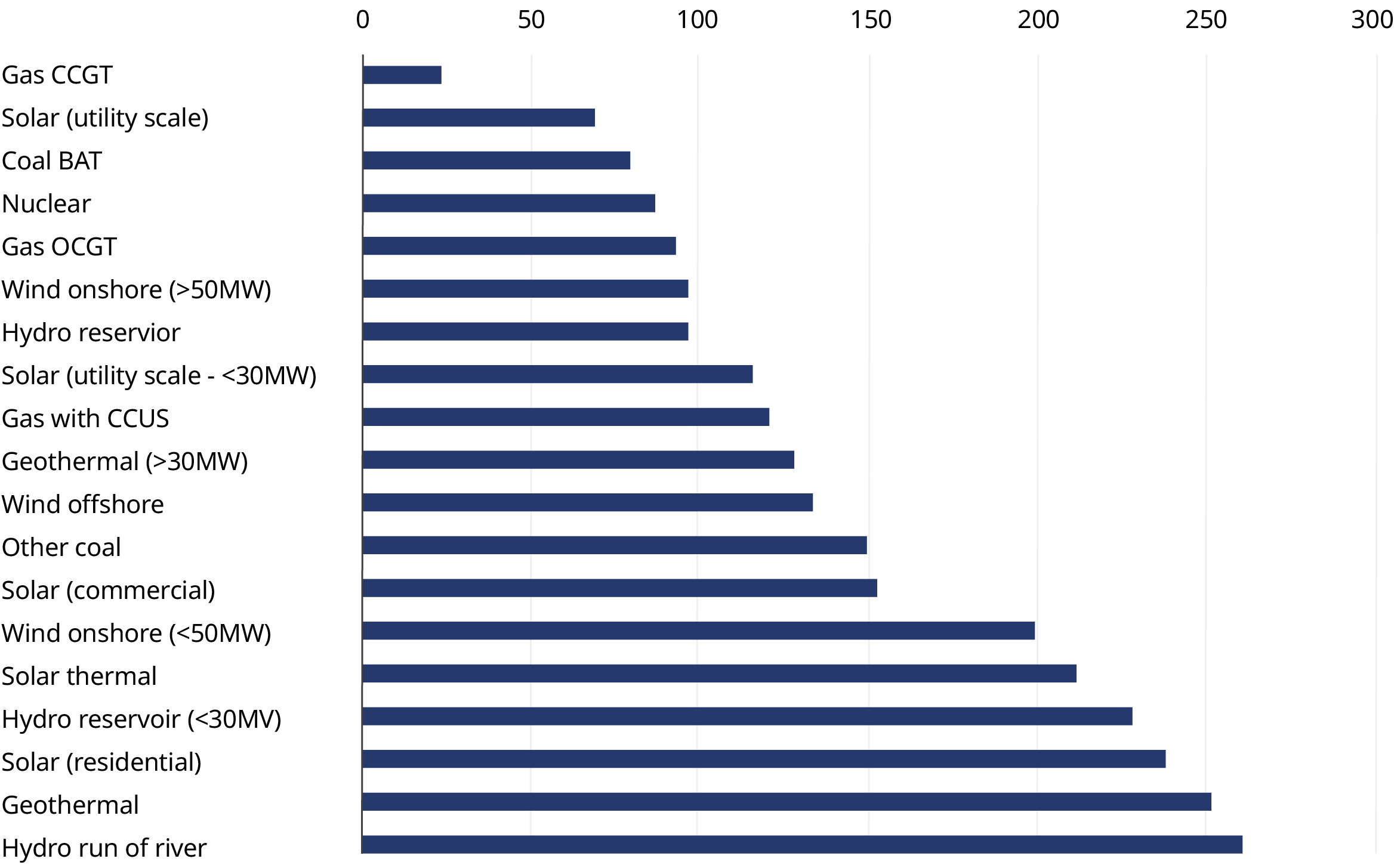

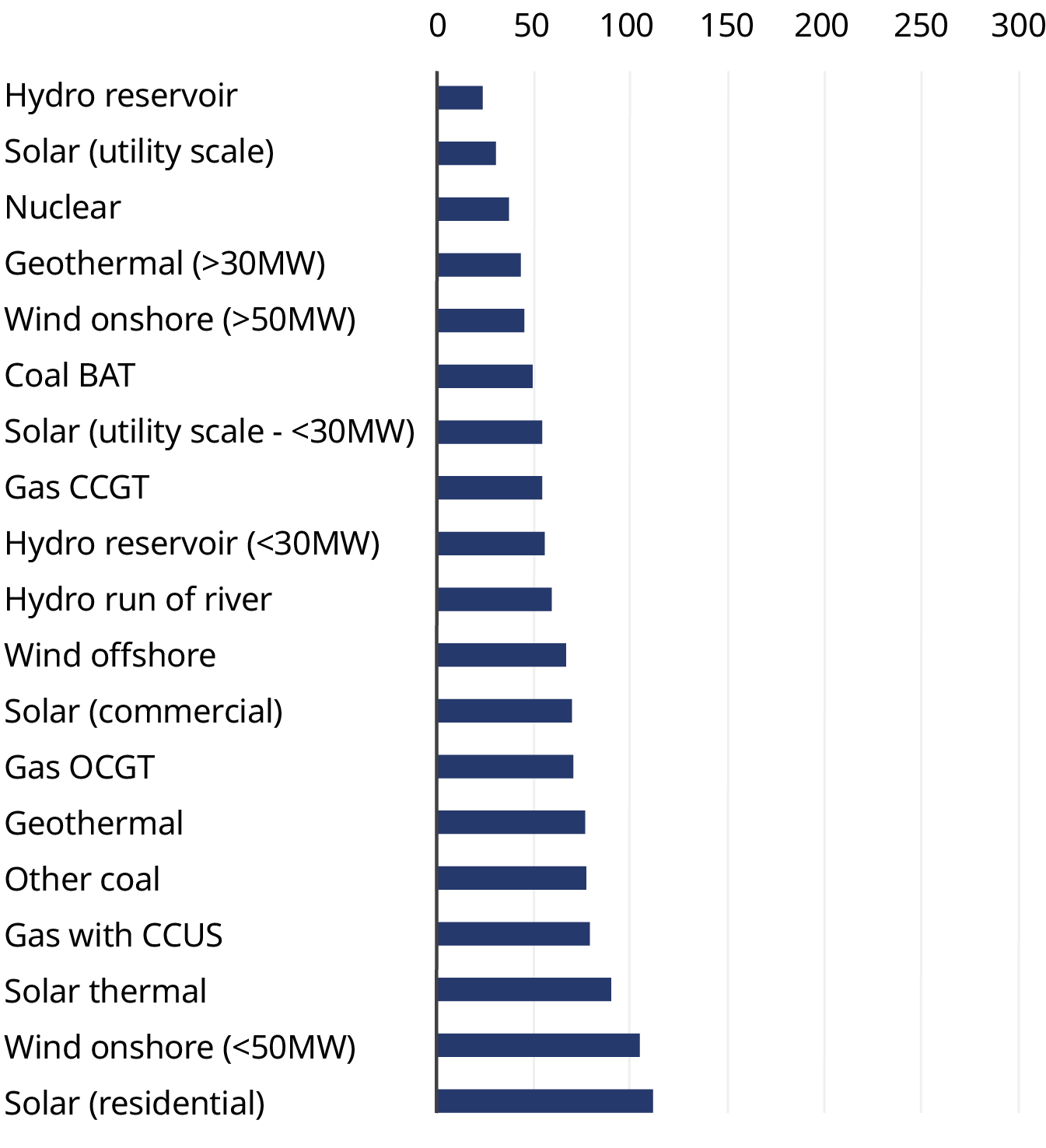

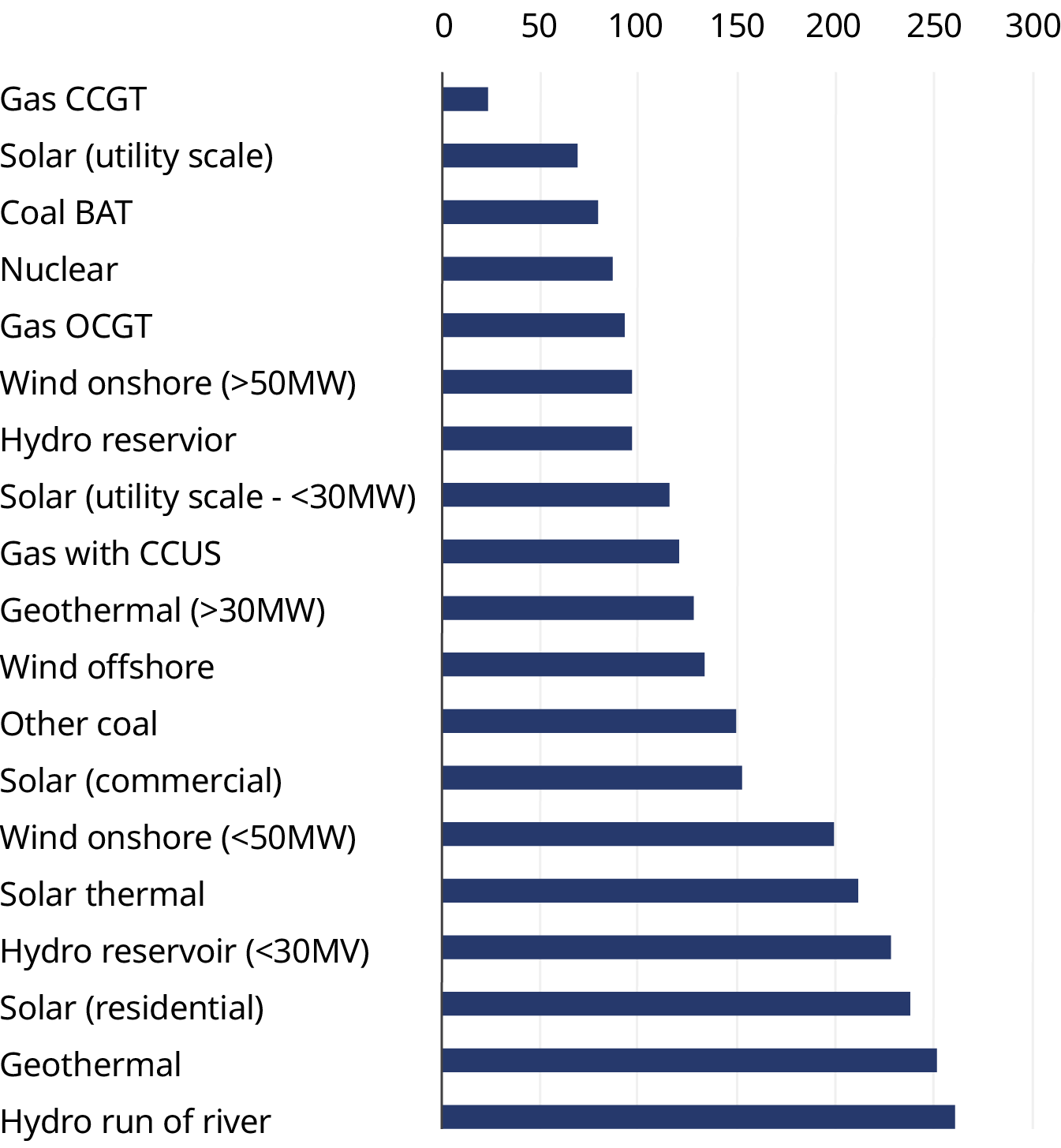

For example, Exhibit 1 shows the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for sources with a low discount rate assumption of 3%, which might apply to a country with low interest rates and low risk investment, for example a project with guaranteed offtake in Japan; and with a higher discount rate of 15%, which could apply to a higher risk investment in a higher interest rate environment, for example an open market project in Indonesia. Energy is materially more expensive in higher interest rate environments, and the relative attractiveness of fossil fuel generation and renewable sources changes with higher interest rates.

The future expectations of how energy will evolve will also change the investment case. For example, an investor looking at the energy evolution in Europe and the United States, where the use of coal-fired power is decreasing, could reasonably assume that the same would happen across other markets committed to energy transition. This immediately makes renewable energy a more attractive investment in that country. In other words, credible commitments to energy transition become self-fulfilling prophecies when interpreted by rational investors.

Key challenges include intermittency to infrastructure, and asset impairments

The above analysis does not always hold; intermittency, infrastructure, and impairments can create complications.

The challenge of intermittency in renewable energy production

Because solar power can only be generated when the sun shines, and wind when the wind blows, they are intermittent sources of energy. At a system-wide level, this creates challenges, because renewable power supply is inconsistent. To work around this, electricity can be generated during the country’s windy or sunny periods, and the excess can be stored for use in latent periods. Indonesia is currently building on its storage capacity through the planned/ongoing installation of 5 MW battery energy storage systems (BESS), linked to PLN’s renewable sites. Indonesia is also building its first utility-scale integrated solar and energy storage project in Nusantara.

However, the need to store energy has implications for the traded energy markets, because an excess of power results in pricing volatility, which works against renewables — solar power in particular sells into the system during periods of excess supply, which is also when pricing is at its lowest. At a certain critical level of supply, this can neutralize the economics around the lower cost of production for asset owners and investors.

These challenges change the economics of production at a system-wide level. One solution is to load the cost of storage onto renewables pricing (by calculating a levelized cost of storage), but to do so would flip the relative attractiveness of renewables compared with fossil fuels.

Upgrading infrastructure for seamless renewable energy integration

At a system-wide level, adding renewables means more energy needs to be generated across all sources to distribute power more equally across the grid. Renewable assets generally generate less power than fossil fuels, and are therefore usually deployed at a smaller scale. That means the power grid needs to be able to cope with a mix of renewable sources adding different amounts of energy to the grid from multiple directions. In markets where renewable energy is only available in some locations, it is critical that the grid connects all the generation assets to where the power is needed. Indonesia’s fragmented geography makes this more difficult and will require a significant upgrade to the existing infrastructure.

Managing asset impairments in Indonesia’s energy transition

Indonesia already has fossil fuel power generation assets. If renewables are installed at scale, the profitability of those existing assets decreases. Furthermore, the age of the assets influences the amount that would need to be written off against how much more the asset might otherwise have produced. This is further complicated by the need for a “baseload” to cover intermittency. For example, there may be a need to run some fossil fuel assets at a lower capacity to maintain an even energy supply over periods when renewable supply naturally decreases due to environmental factors. This also puts a premium on conventional assets that can be easily turned on and off, such as natural gas, but not coal.

Key steps for advancing Indonesia’s clean energy goals

Challenges persist, but it does not mean there are not good opportunities. Renewable capacity built on site for industrial use avoids many of the challenges by creating a guaranteed source of offtake, which reduces risk and thus financing costs. It also sidesteps the grid by directly using the generated power, and it does not need to consider the implications to asset owners or the macroeconomy. This creates a rich vein of investment opportunities because energy intensive industrial developments can invest in capacity that will lower their energy costs and reduce their consumption. It is also not new — Indonesia already has examples where aluminium smelters are situated next to captive hydropower, precisely to lower energy costs.

Other projects that are immediately investible will have similar characteristics — guaranteed offtake (which could also be with utility scale buyers), a realistic approach to transmission and distribution, and low financing costs. The use of government or international development money could be deployed as equity (or, better still, off balance sheet as guarantees) to reduce risk in the projects and financing costs.

They also point to a set of policy and private sector collaboration initiatives that can efficiently accelerate the transition. We suggest four in particular:

1. Prioritizing renewable energy for all new capacity

While there are challenges to impairments, this does not change the marginal economics of new capacity, where it is clear there is no longer a case for building new fossil fuel generation. New capacity should all be renewable.

2. Strengthening grid infrastructure and storage for a renewable future

Infrastructure is the biggest operational impediment to a faster, cost-saving transition to renewables, and should be the focus of policy-led investment. By moving to a well-connected, high capacity, multi-directional grid, Indonesia can prepare for a future of renewables. That means crowding in private investments, which in turn means creating business cases for public-private partnership deals. Investing in storage is also a prerequisite.

3. Deploying the off-balance sheet to lower financing costs

Money needs to be spent on generation capacity, but it does not need to be state or development money. Government money is better spent on infrastructure, while its balance sheets should focus on how to best reduce the risk in generation projects. Guaranteed offtake agreements, credit guarantees, cross-currency guarantees (to allow projects to be funded in foreign currencies rather than in IDR, thus reducing interest rates), or creating innovative capital market funding solutions can all accelerate the transition without breaking budgets.

4. Driving investor confidence with clear energy transition targets

Investment decisions depend on future expectations of capacity usage. Governments and the private sector can develop and announce net zero targets and transition plans. In this regard, Indonesia is behind many of its regional peers, which have used the soft power and investor influence of the state to push domestic banks and large industrial companies to make decarbonization plans. This, in turn, builds a clearer picture of future demand, which changes the investor calculation. Through the Ministry of State Owned Enterprises, OJK, Bank Indonesia, and other players, Indonesia undoubtedly has the means to do this.

The future of energy is increasingly clear — it will be renewables-focused, lower cost, and cleaner. It will require a radical upgrade in infrastructure and storage, but it is environmentally and economically desirable. When macro-trends become obvious, it pays to be near the front — where one is able to benefit from the investment costs and mistakes of the earliest adopters, but not too late to miss out on industrial and economic opportunities. To achieve this, Indonesia needs a change of pace. We call on both the private and public sectors to take up this challenge, and believe that this will pay dividends for investors and the country as a whole.