Our first article in this series, “The Path To Long-Term Shareholder Value For Rail Is Growth,” outlined the need for intermodal to provide an outsized share of Class I freight railroad industry growth going forward. Since rail already holds a substantial share of the long-haul freight market, the potential for future volume and revenue growth is likely to be highest in shorter haul lanes and lanes that require interchange. To improve market share in those areas, railroads will need to change their operating paradigm for intermodal, resolve interchange issues, and invest in new kinds of rail facilities and freight ecosystems to open new markets.

Shifting focus to short-haul opportunities and interchange solutions

For moves of more than 1,500 miles on the railroads, using existing terminals and domestic equipment (53-foot containers and trailers), rail already accounts for 39% of the US addressable long-haul intermodal market. Long-haul is the segment where rail intermodal is most competitive, and while there will continue to be long-haul opportunities, there is not enough addressable volume left to deliver a step-change in railroad growth. (The majority of what goes by truck over 1,500 miles today either requires faster transit times than intermodal offers or would be highly complex to serve).

As shown in Exhibit 1, nearly 31 million truckloads move today in lanes under 1,500 miles that could potentially be shifted to single-line rail intermodal. A further 7.6 million truckloads could be converted to rail intermodal if the industry can solve today’s interchange service gap.

Medium-haul lanes and revenue growth

In medium-haul intermodal lanes (750-1,500 miles), where rail intermodal currently has a 27% share, improving interchange performance to reach the penetration levels of single-line rail could add an estimated $1.7 billion in annual industry revenue. A key challenge for railroads is finding a way to offer truck-competitive intermodal service to cities within the Mississippi River watershed. This zone acts as a “great divide” between the eastern and western rail networks and presents challenges in service and economics that railroads must overcome. Any new offering involving interchange must work for both parties, but must we really accept transcontinental mergers before we find a way to take this freight onto rail?

Rethinking terminal operations

The largest but most difficult opportunity for railroads is in intermodal lanes of 250 to 750 miles. Currently, railroads only carry about 11% of addressable intermodal freight under 750 miles. We estimate that rail intermodal could serve as much as 27 million out of 41 million total truckloads in these lanes, simply using the existing terminal and railroad network.

However, given the congestion and heavy overhead of existing intermodal terminal operations that are designed for long-haul operations, it may be necessary to consider other paradigm-breaking alternatives for these short-haul lanes to reduce trip costs. Smaller, more flexible terminals placed closer to demand could reduce drayage costs and enable a higher share of miles on more cost-efficient rail. Terminals and operations that do not require trucking carriers to shift to intermodal-specific equipment could reduce complexity costs for shippers. If railroads really want to tap this growth opportunity, new business models might even be required, where capital and risk are shared with third parties.

Many shorter haul lanes are concentrated along the southernmost transcontinental highway in the US, Interstate 10 (where the western railroads have historically focused on long-haul traffic), as well as east of the Mississippi (Exhibit 2).

A paradigm shift for intermodal

As discussed in our prior article, the Class I railroads need to grow to maximize long-term shareholder returns and other economic and public benefits, including lowering greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and reducing highway congestion and maintenance costs. Increasing intermodal volumes as an engine of growth will require truck-competitive service in shorter lanes, interchange collaboration, and a new approach to terminals and train operations.

Offering single-railroad truck-competitive intermodal service in lanes under 750 miles would mean delivering consistent arrival times, planned schedules to match shipper needs, and fast transits, such that intermodal channel partners could guarantee shippers reliability matching that of truck, with no more than one extra transit day.

Where intermodal trains must interchange between railroads (for example, between western and eastern carriers) shippers consistently experience a higher degree of service failure. A concerted effort to collaborate and streamline interchanges, so as to match the service levels of single-railroad hauls, would open up new lanes in the Mississippi watershed, where the densest truck lanes cross between eastern and western railroads.

A new approach to terminal and train operations may be required for rail to be cost competitive with trucks in shorter lanes. The industry’s current model for long-haul intermodal — large terminals and long double-stack trains — is capital-intensive and necessitates high volumes to be profitable. In particular, adding smaller terminals closer to freight centers for medium- and short-haul intermodal (ideally integrated with logistics parks) would enable faster, more reliable door-to-door service at a lower cost, by reducing the drayage which makes up a high percentage of short-haul intermodal costs.

A final consideration is that increasing regulation of GHG emissions could give railroads and their intermodal channel partners a boost, since even shorter haul intermodal could help shippers reduce their CO2e emissions. Intermodal is currently the only way for a shipper to reduce its over-the-road trucking emissions by more than 40%. Of course, shippers will not switch solely for emissions benefits; reliable and cost-effective service must be on offer first.

The short-haul revenue prize

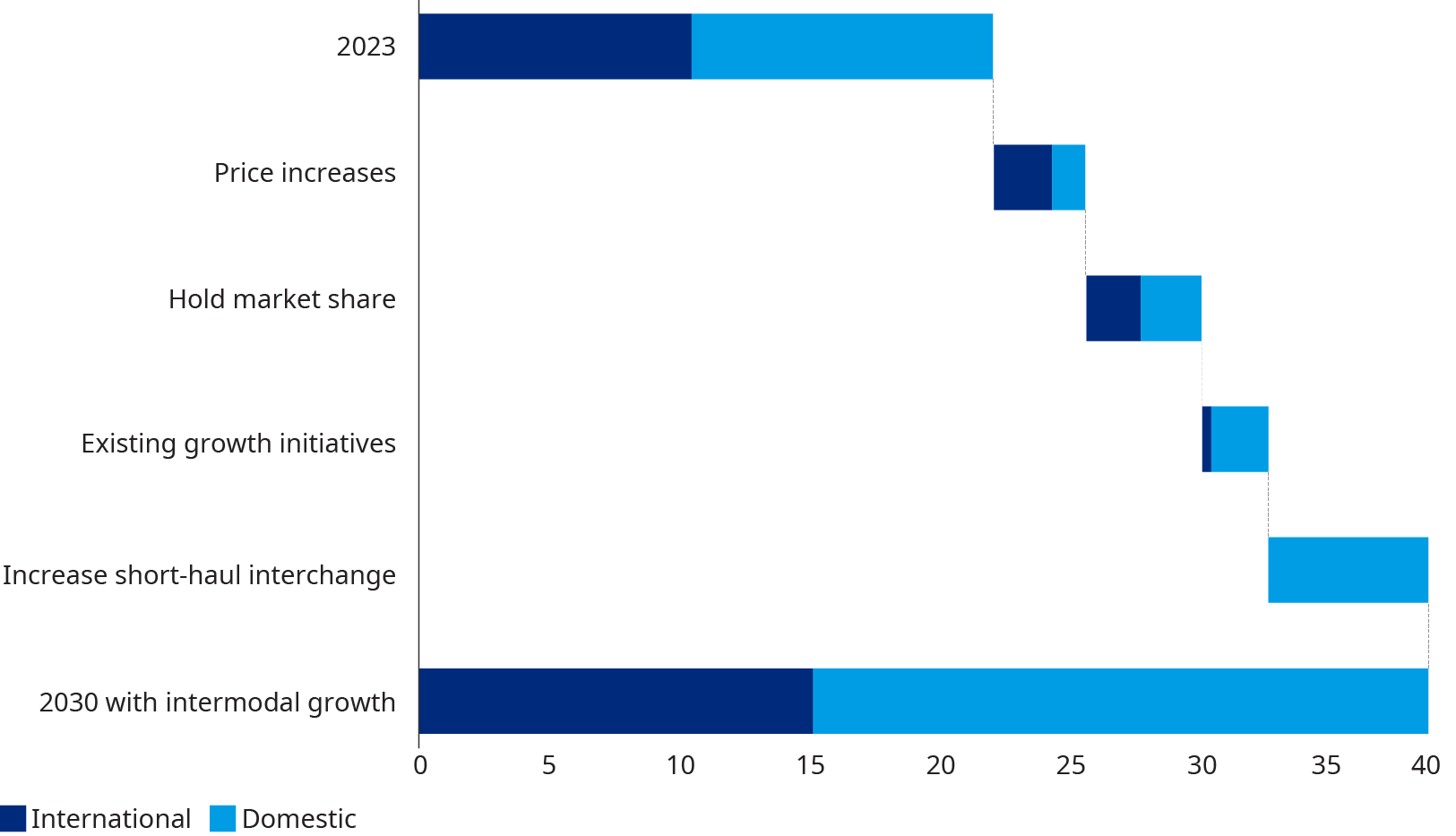

We previously projected that “business as usual” price increases and holding market share could increase rail industry revenues from intermodal by about $7.6 billion from 2023 to 2030. Another $2.4 billion could be realized through recently announced initiatives, including new transborder and interchange services. Both BNSF and UP are investing heavily to better serve the huge import market of Southern California. Short-haul intermodal from the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach to new inland facilities (such as BNSF Barstow) also could feed the domestic intermodal segment.

Embracing domestic short-haul and medium-haul intermodal is the final piece of the puzzle for rail. To achieve the growth scenario of $37 billion in revenue by 2030, the railroads would have to boost intermodal revenues by nearly $6 billion (Exhibit 3). To get there, they would need to convert approximately 20% of truck traffic in the densest US city-to-city truck lanes over 300 miles to intermodal and solve the medium-haul interchange problem — principally in the Mississippi watershed.

Intermodal is the only industry segment that the rail industry serves which has the addressable freight to grow fast enough to offset continuing declines in coal volumes. But to adequately expand the size of the revenue pie by 2030, the railroads should consider embracing an “and” strategy. They must grow both intermodal and industrial products. This will require changes in status quo operations, product offers, and potentially go-to-market strategies. It will not be easy, but there are real rewards for shareholders, shippers, and other supply chain stakeholders from sustained rail growth.