Going, going, gone? Between 2012 and 2021, US banks closed 15% of their branches, while EU banks shuttered a staggering 36%, or 80 000, branches, according to the European Banking Federation — and they are not done yet.

The logic is simple: Customers are visiting branches less and less. If customers don’t use branches, banks can save money by closing them.

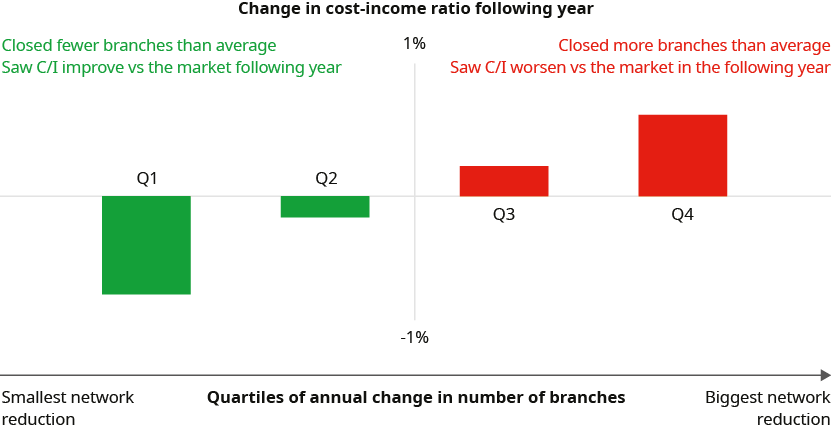

Following this logic — that closing branches is good for business — then it stands to reason that the banks that close the most branches should see the biggest gain in efficiency. However, that’s not what the data shows. If anything, the opposite is true. Over the last four years, US banks closing branches at a faster rate than the market average in one year saw their efficiency worsen the following year, compared to the market. Conversely, banks with fewer closures saw above-average improvements in efficiency.

What is going on? There are many possible answers, but Occam’s razor suggests that the simplest answer is usually the correct one. In this case, the simple answer is that the simple logic presented before is simply wrong.

Just because customers use branches less doesn’t mean they value them less. We know customers value branches both from what customers tell us and what they do. When banks close branches, attrition goes up and stays higher for years, while new account openings locally go down.

Sometimes the cost-savings from closure outweigh the overall customer impact — but sometimes they don’t. The evidence suggests that some banks, at least, are choosing the wrong branches to close.

This matters. Any gardener will tell you that pruning the wrong branches kills a tree. The same is true in banking. Bank branches are expensive, but they are key for banks to thrive in the foreseeable future. Closing the wrong branches leaves a bank at a sustained disadvantage versus competitors.

What is the underlying cause of the problem? Most banks use some sort of model to optimize their networks, but our experience with clients globally is that many of these models are flawed.

5 ways banks can optimize their branch networks

1. Focus on existing customers, not potential ones

If you are building a new network, it makes sense to start with high potential local markets, with the challenge being to estimate potential. This is Greenfield modeling. But banks are not building a new network, they are optimizing an existing one. Now, for a general retailer, potential modeling still works, so that’s what most off-the-shelf solutions do. But banking is a more complex: Unlike retailing, banks make their money off products sold in the past. As such, “Today’s cost is tomorrow’s revenue,” with only a small fraction of income coming from new customers or sales. In mature markets, most of the population is already banked and switching is low. In the UK, as an example, only some 3-4% of the population is available for acquisition in any given year. As a result, modeling needs to focus primarily on the impact on existing customer base, with potential new customers influencing marginal cases — not the other way around. This is Brownfield modeling. This is a case of when going green is not good.

2. Focus on the network, not individual branches…

Banks often look at metrics such as the branch P&L (profit and loss), sales, or customer visits when assessing a particular branch. There are two problems with this. First, these metrics paint a picture that is at best incomplete and at worst misleading. Branch P&L depends on cost allocation and changes in the base rate, while many sales influenced by the branch are completed digitally and vice versa., overall branch visits are swamped by cash and simple interactions. Under 5% of customer visits to the branch relate to support interactions, where the customer needs help to decide what to do, and where customers really value human interaction. Second, in a network, you have network effects. That means you cannot view branches in isolation but need to look at the impact of each branch on the network as a whole. Rather than asking how much a particular branch contributes on a standalone basis, the real question is how much aggregate business is lost if the branch disappears. This means understanding travel time to alternative branches, the willingness of customers to travel for the interaction that they wish to undertake, the number of customers affected, and their value. It also means understanding the impact on surrounding branches as remaining customers and transactions flow from one branch to another, hitting both costs and service levels. Focus on the network, not the branch.

3. …But think in terms of modules

Even with a network approach, most models look to help answer the question of whether to have a branch in a location. That’s a binary decision that misses the point. As discussed in our Banking on Humans paper, there are three broad reasons why customers currently go to the branch: cash, execution, and support. Each of these interactions requires different infrastructure and people-skills in the branch. At the same time, customer willingness to travel varies by service, being generally more prepared to travel for quality advice and help than for simple cash transactions. Rather than deciding whether to have a branch in a particular location, the real question is what services, if any, the bank should offer at that location — that is, what modules. These modules can then be bolted together (like building blocks) to give you an effective branch network with local services tailored to local needs. The result is likely to be a much denser network for cash provision (whether through counters, ATMs, or third parties) than the network for complex interactions. This not only makes sense for the bank, it also helps meet regulatory requirements. Branches are not binary — think in terms of modules.

4. Consider the differences between customers

Different customers use the branch for different reasons and have different sensitivities to travel time for each type of interaction. For example, small businesses need cash-in capability and will switch if it is not readily available locally — almost no-one else cares. Similarly, more customers are prepared to travel for advice, given that these moments are infrequent and have significant value, while others prefer interacting with their advisor remotely. Meanwhile, vulnerable customers need greater access to face-to-face support, and a significant proportion of consumers still use cash so need access to cash-out capability. At the same time, some customers’ business is worth more than others, while the political/regulatory impact of reducing services varies by customer segment. Aggregate modeling misses these differences and given the amount of customer data banks hold, there is no excuse for it. Customers are different — don’t think they are all the same.

5. Remember the market competition

Customers who leave your bank, switch to a competitor. The likelihood of them switching depends on the available alternatives — or the next-best offer. Despite this being obvious, many network models ignore competitor presence. Sometimes customers will switch to a digital provider, but more usually they switch to another high-street bank. In fact, public data in the UK shows that roughly 95% of customers who switch, switch to another high-street bank. Put another way: Where there is a local alternative, closing a branch will lose you more customers. Importantly, the biggest impact is whether there is a local alternative at all — with the number of competitors being much less important. Banking is competitive — don’t forget the competition.

These five fixes can sound like a lot of work. Is it worth it?

First, don’t think of the work as incremental. Each of the improvements gives you a better understanding of your network and each improvement is more about using a better underlying conceptual framework in the model, rather than overly complex modeling. That same framework provides additional insight for other decisions you make. Your network is one of your largest cost items and is also arguably one of your greatest competitive weapons. Any additional insight is valuable. Second, remember the lessons from the US experience. Closing the wrong branches isn’t just unfortunate, it is costly. It needlessly loses you valuable customers who will not come back, alienates others, and shrinks your advantage versus digital players. Pruning the network is necessary – but do it sensibly. Get it wrong and risk that it is not just your branches that are going, going, gone.