The infrastructure sector today faces a complex landscape of global risks. The 2020 Global Risks Report (GRR), an annual report published by the World Economic Forum with support from Marsh & McLennan, warns of a chronically unsettled global landscape – one that businesses cannot expect will ‘snap back’ to its old normal.

Against a backdrop of continued macroeconomic uncertainty, societal instability, weaponized cyber capabilities, acute environmental threats and geopolitical frictions, infrastructure investors will need to be adaptable to ensure the longevity and security of their assets. Doing so will require an earnest consideration of the World Economic Forum’s call for a multi-stakeholder approach to mitigating emerging risks. The 2020 Global Risks for Infrastructure Map, produced by Marsh & McLennan Advantage Insights in partnership with the Global Infrastructure Investor Association (GIIA), provides some guidance for investors looking to navigate the choppy waters ahead, based on key data shown in the 2020 Global Risks Report.

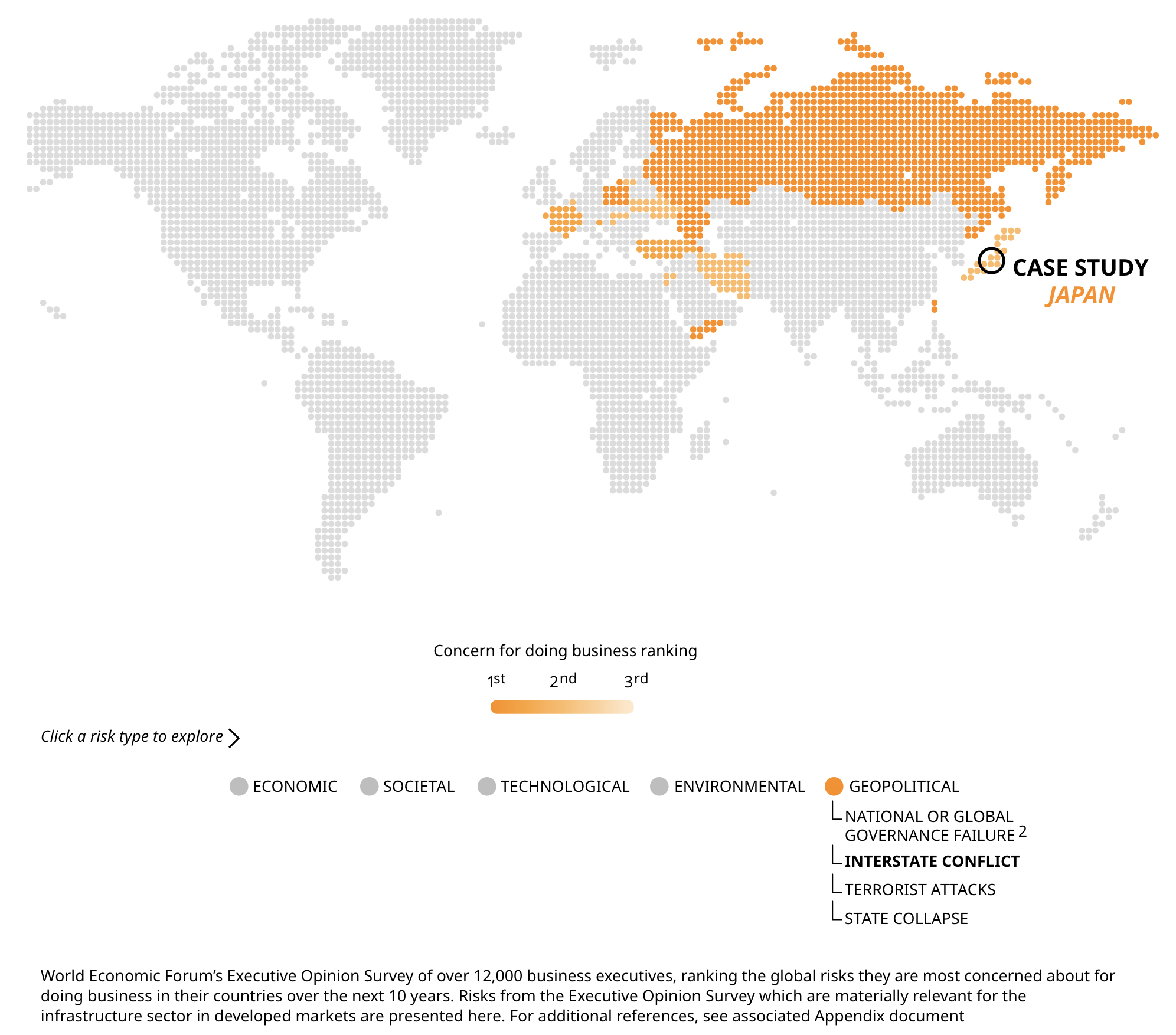

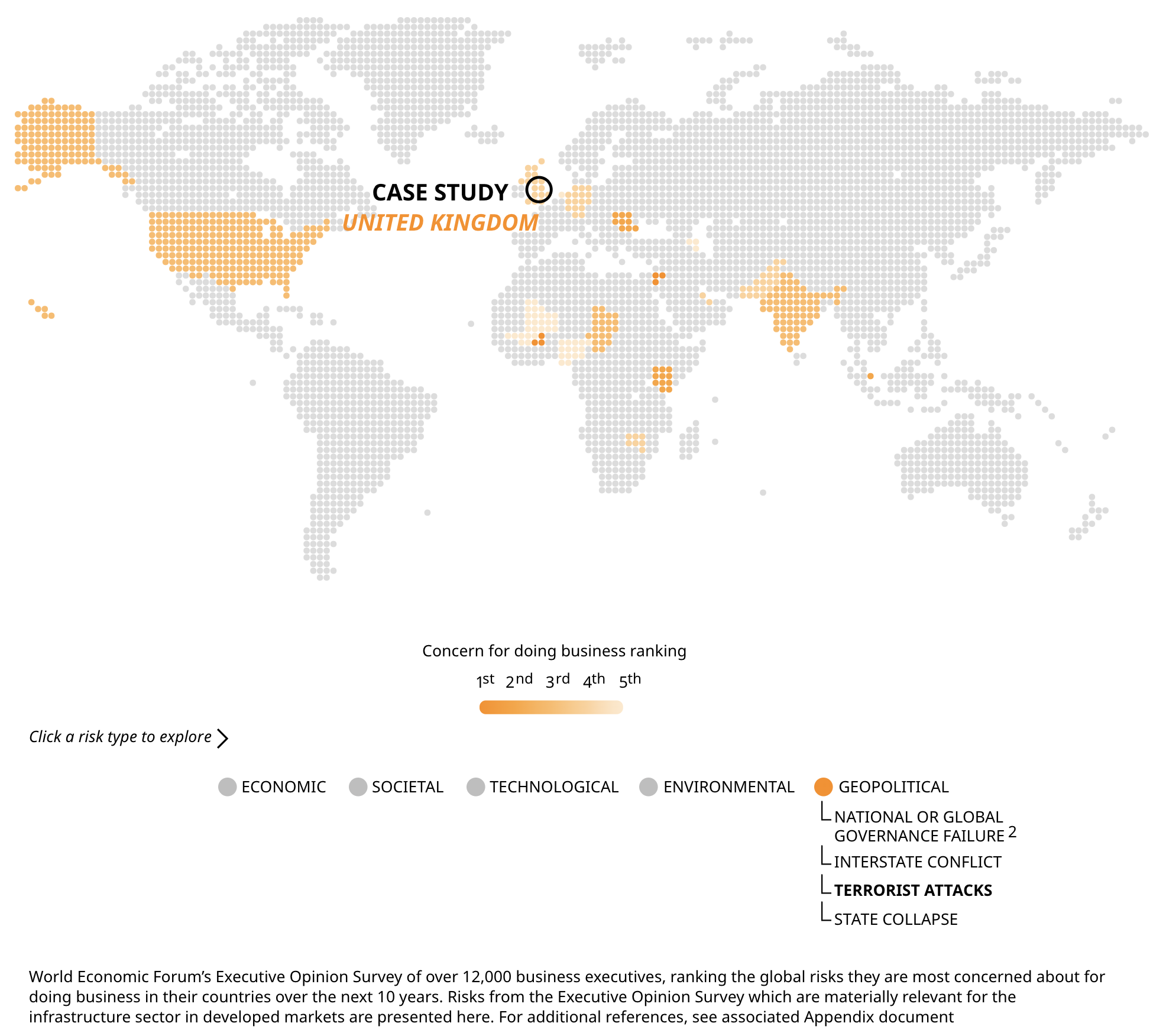

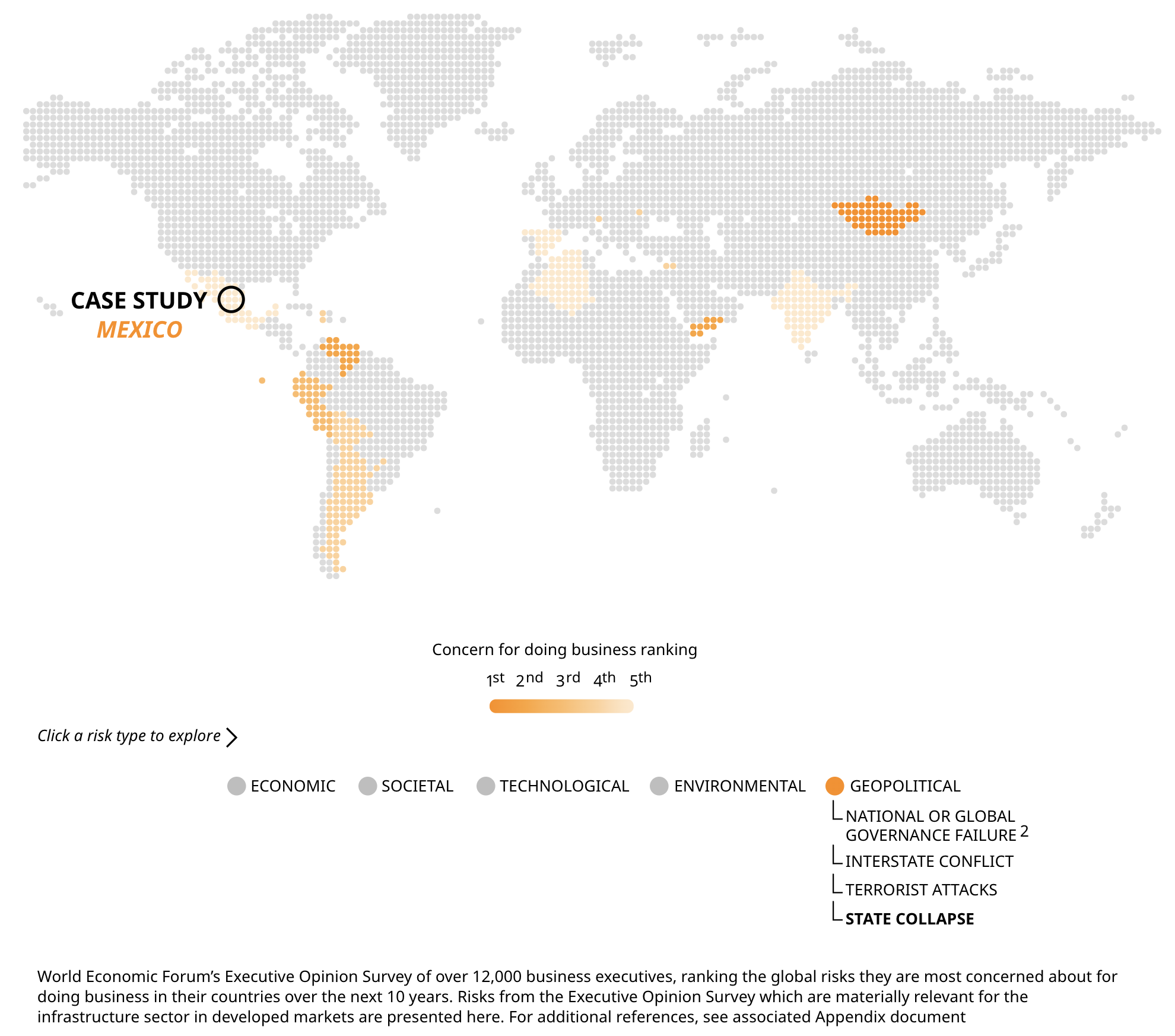

Risk Profiles: Explore key markets at risk

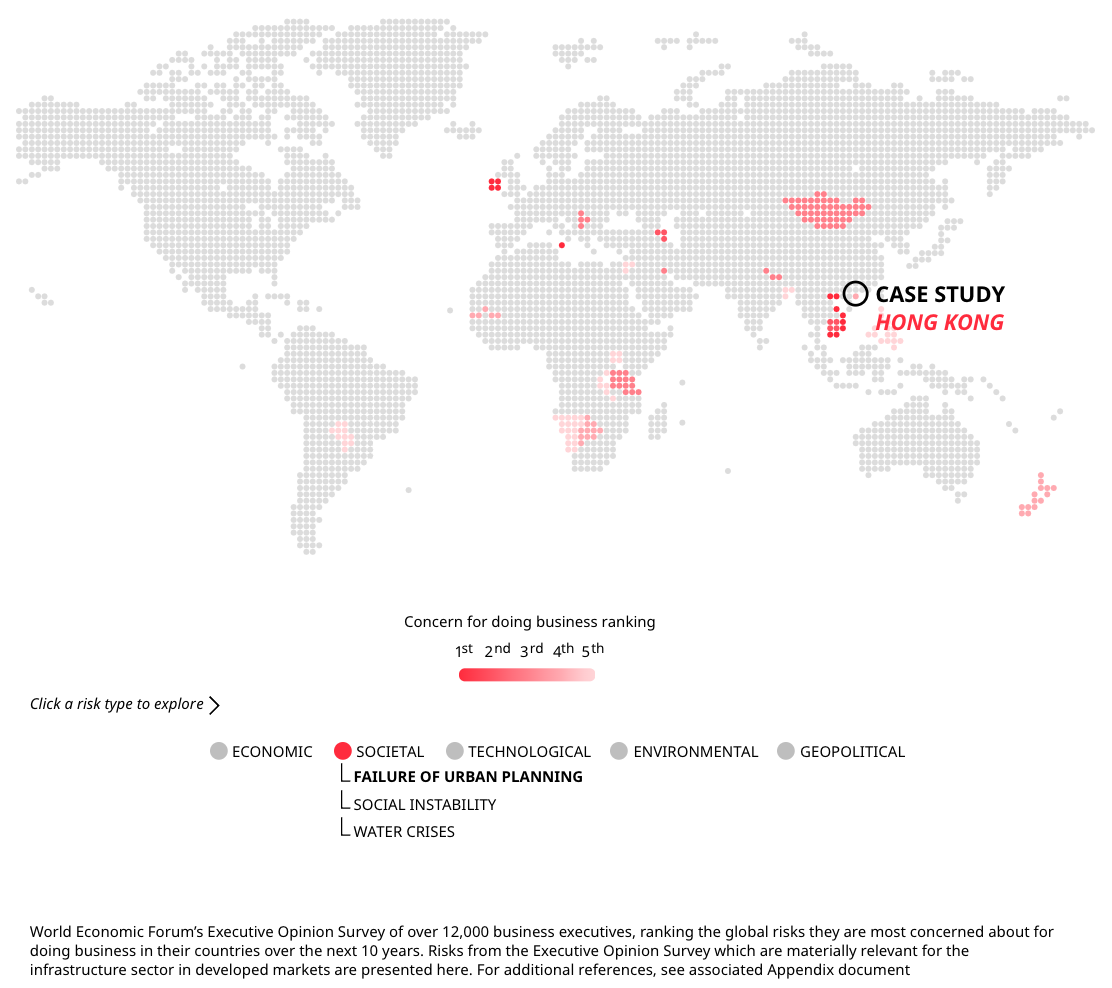

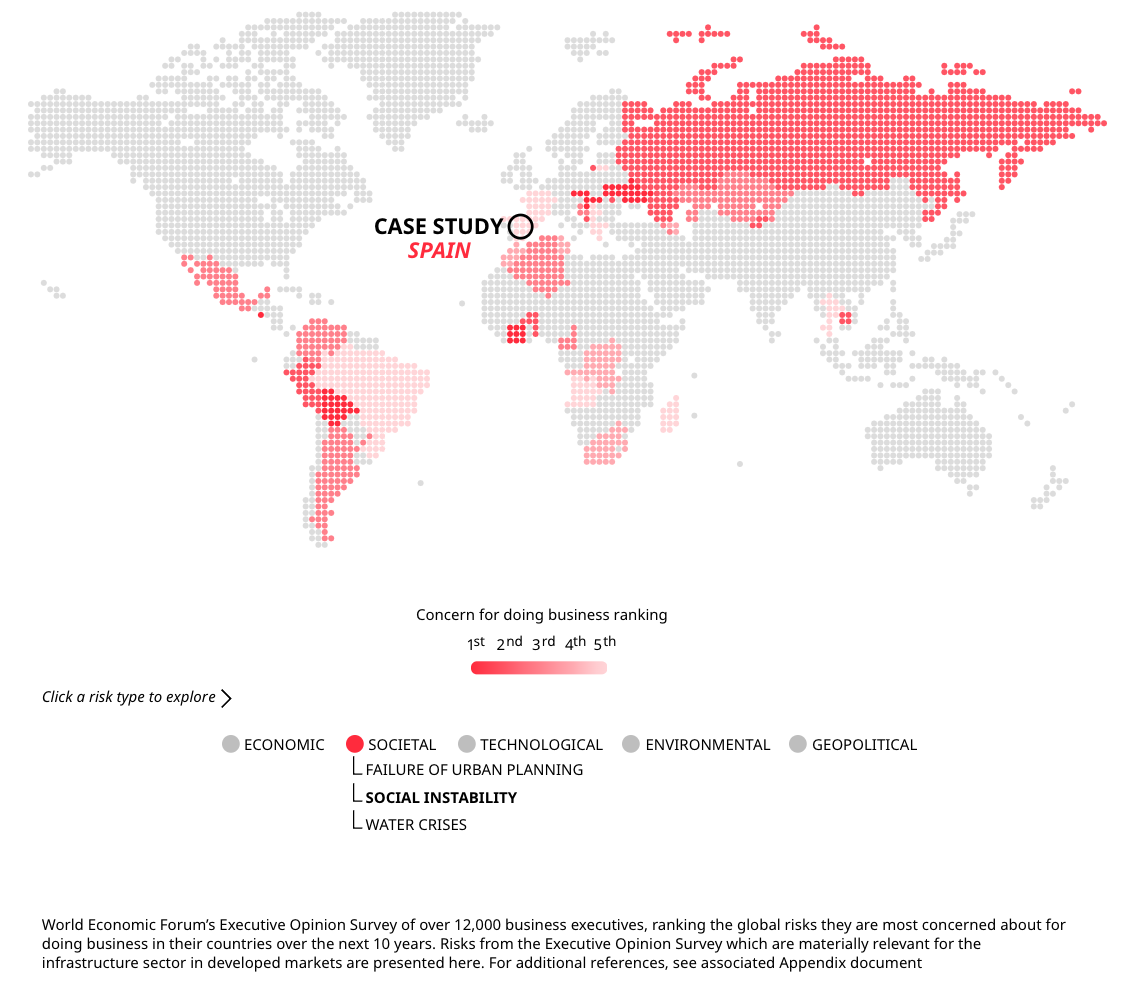

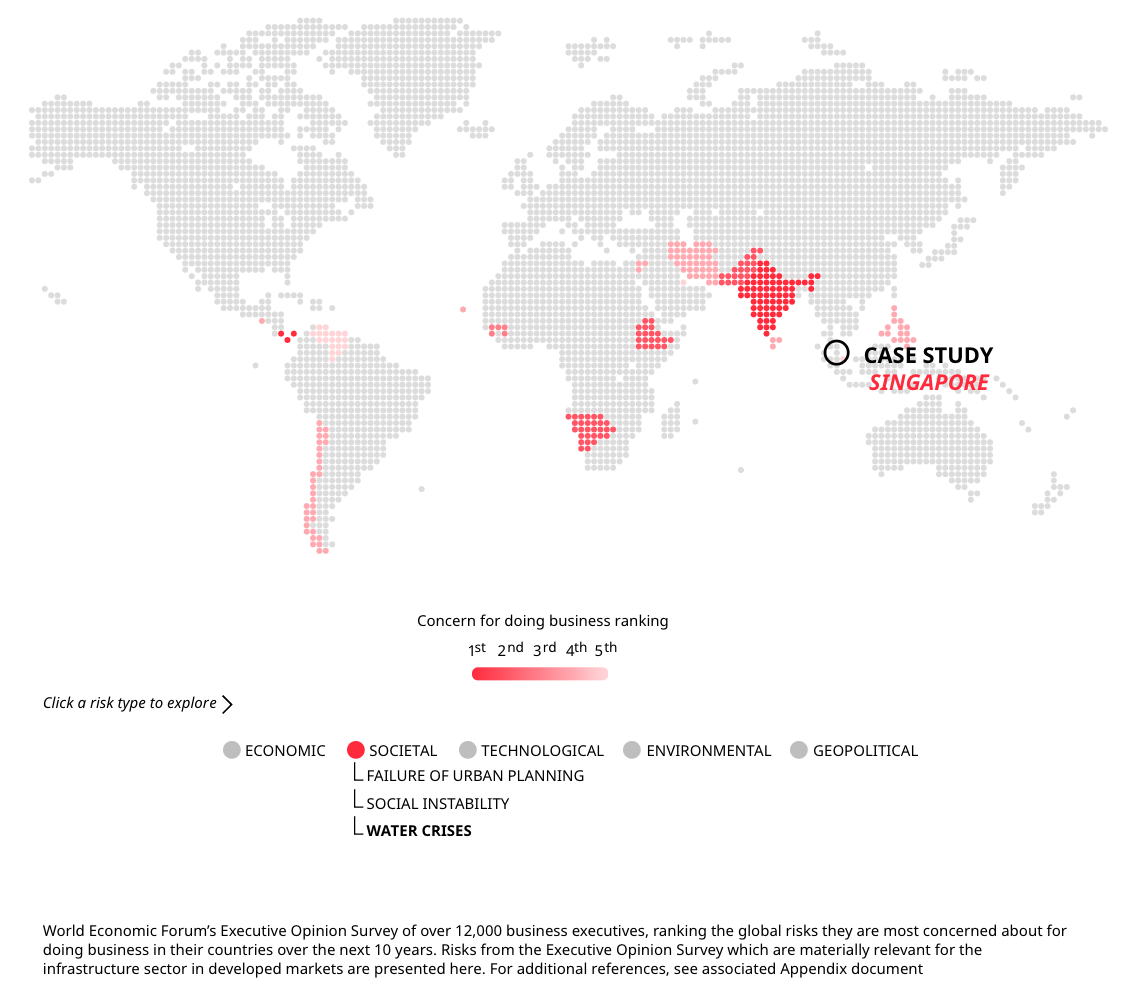

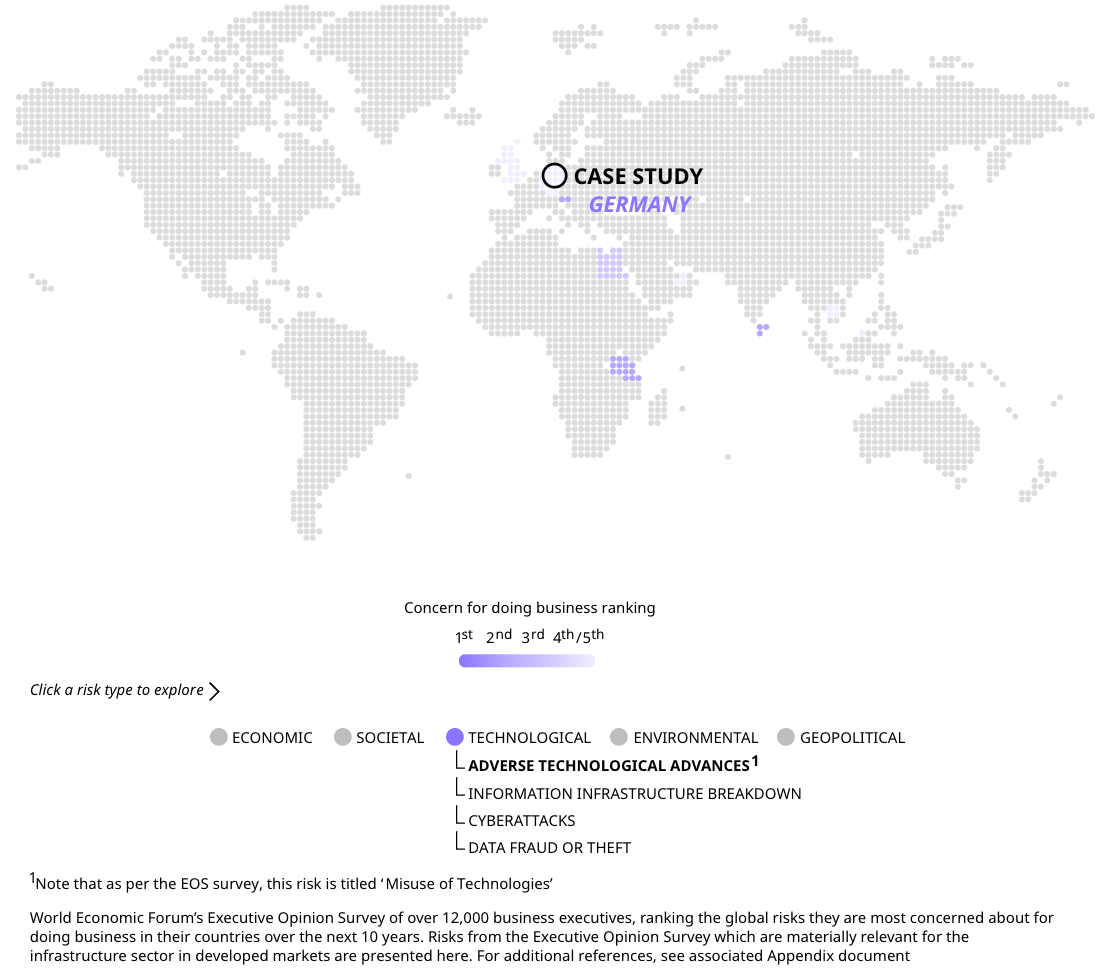

The first page of the 2020 Global Risks for Infrastructure Map provides investors with a view of the key risks presented within the GRR (referred to here as ‘global risks’) with material relevance to the infrastructure sector, and the markets where business executives believe these risks are of high concern.

This page also includes a curation of case studies evaluating ways in which these risks have affected infrastructure assets in recent years. These case studies have been carefully selected from key infrastructure markets where concerns regarding global risks loom large on the horizon.

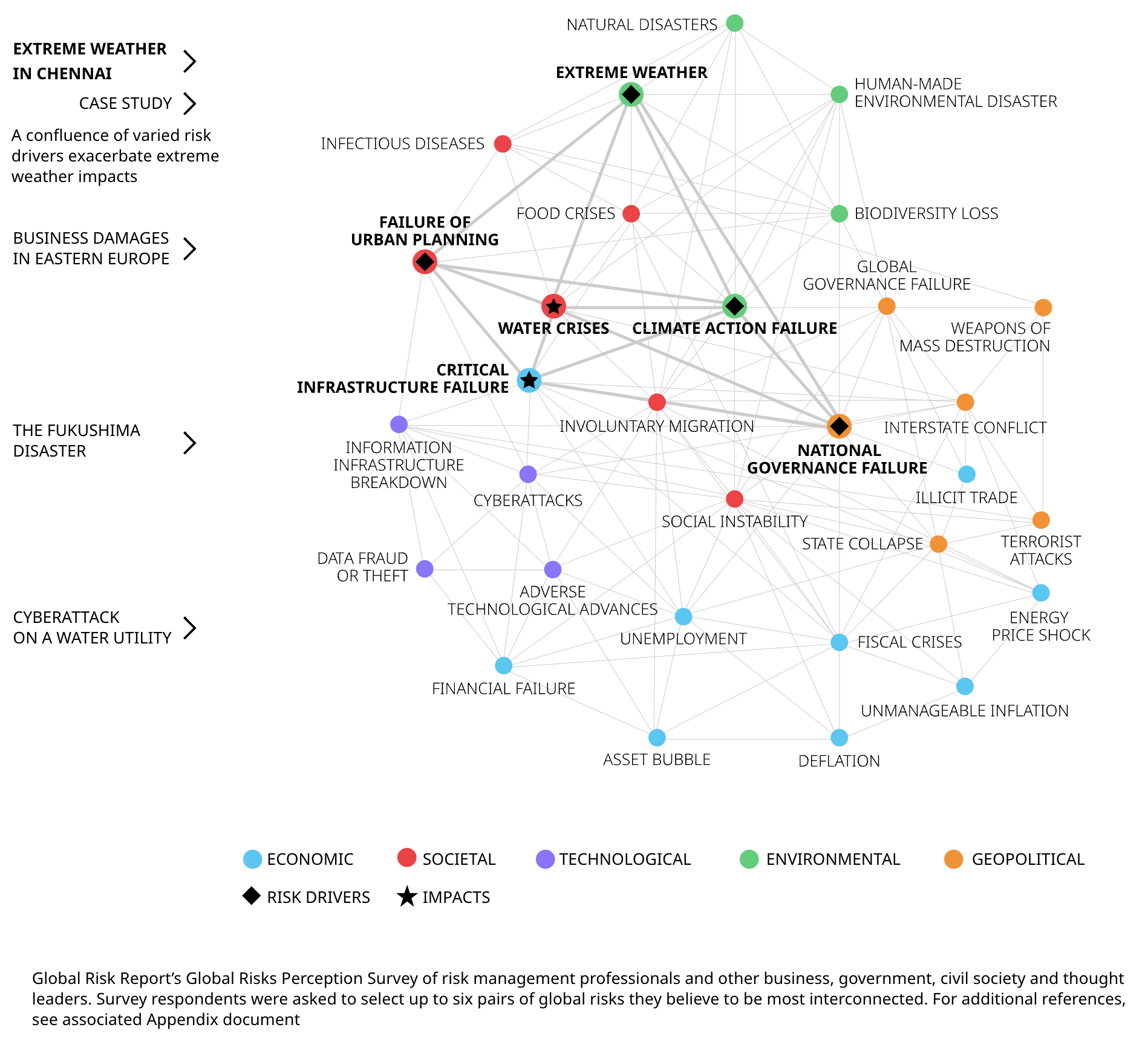

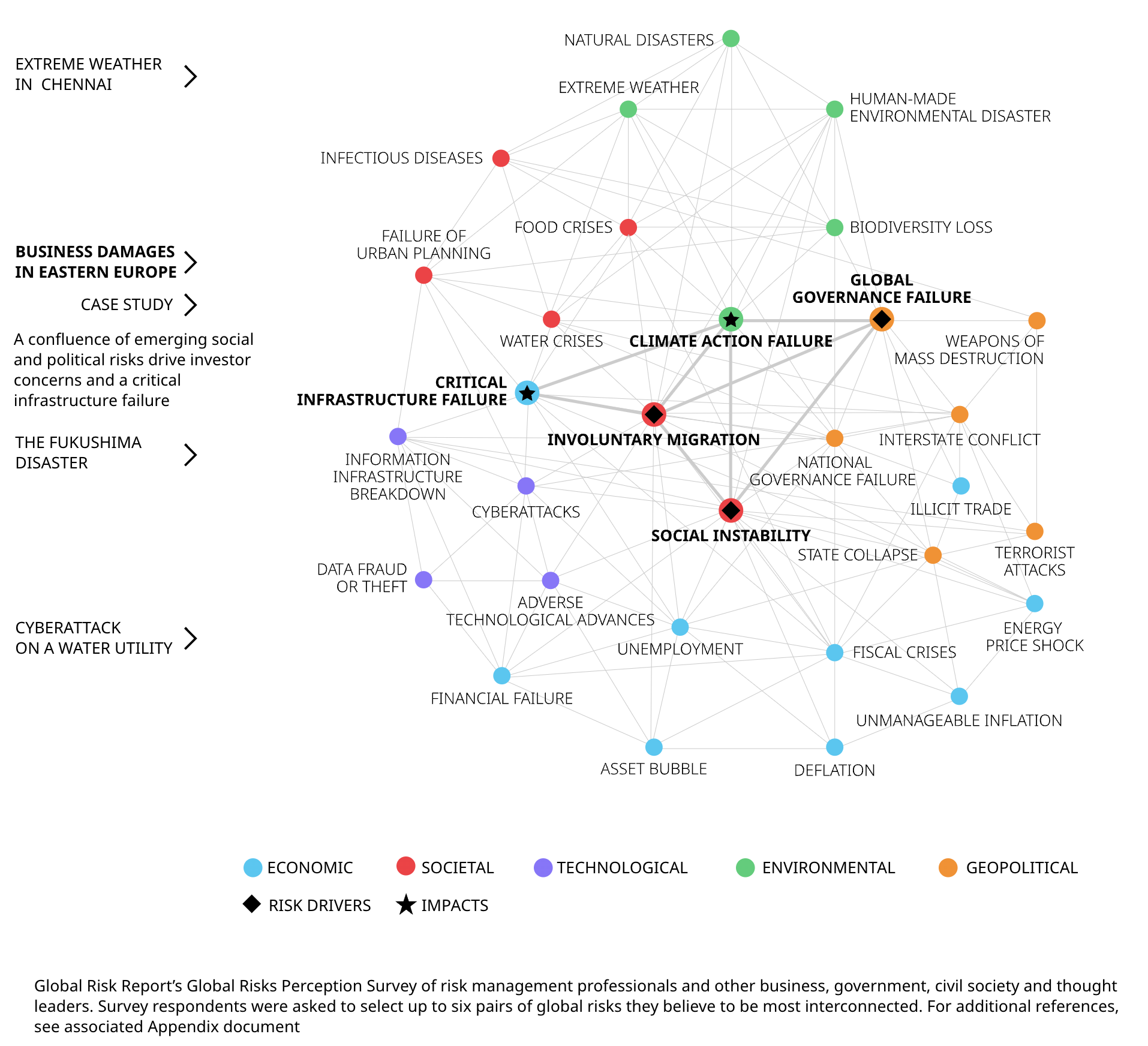

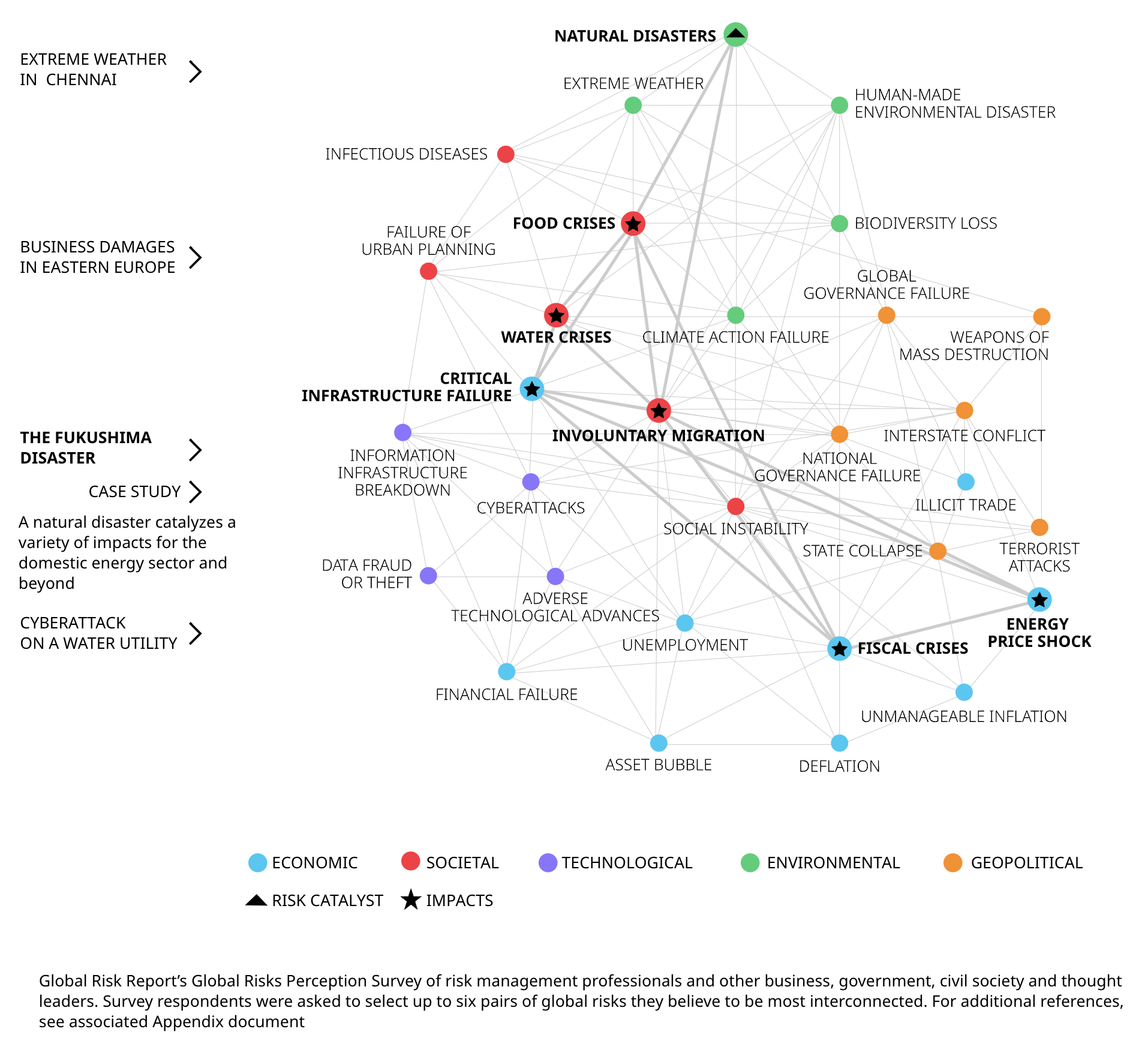

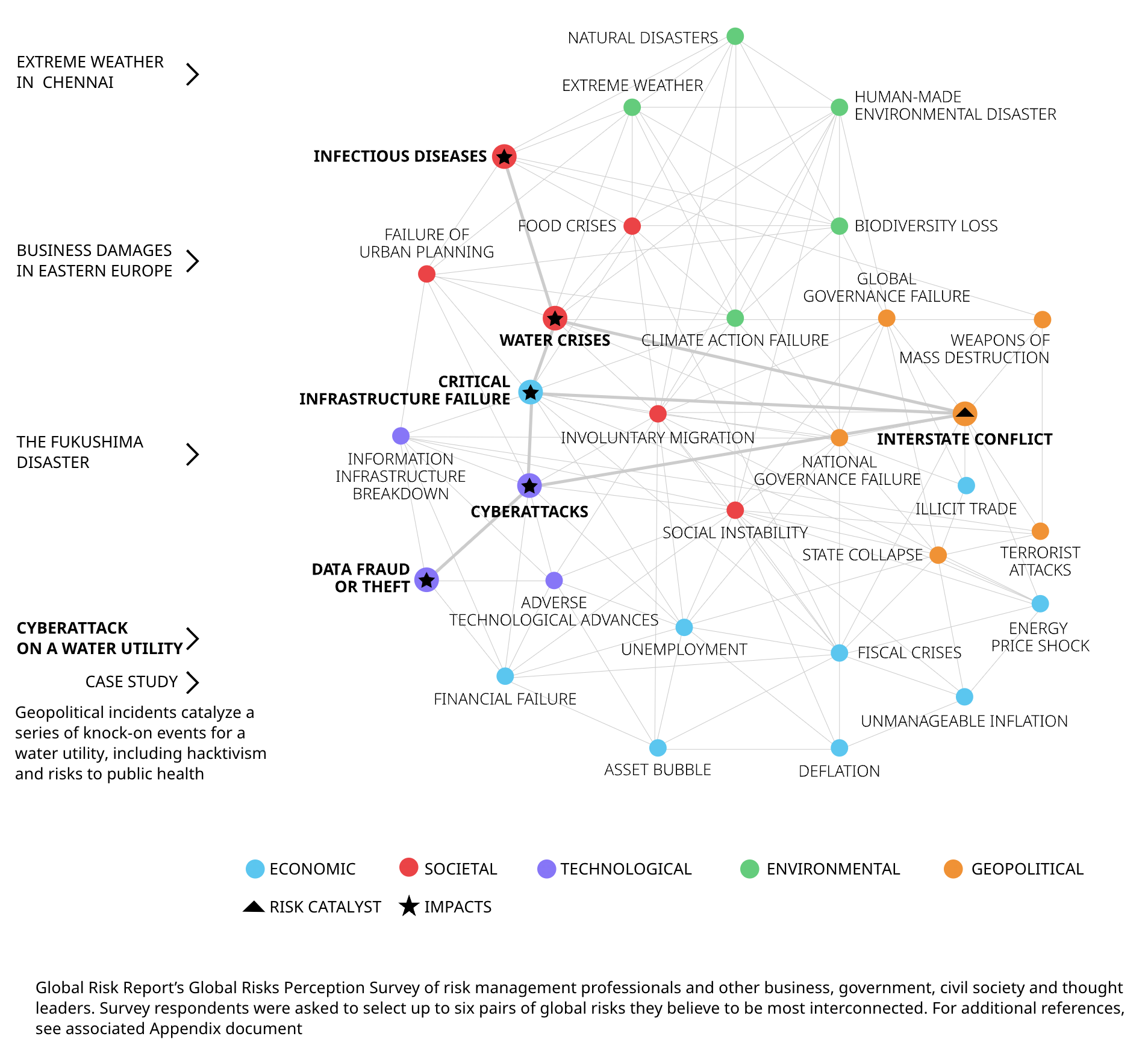

Interconnections: Explore interconnected risks

The second page of the 2020 Global Risks for Infrastructure Map provides an even broader view of the global risks infrastructure investors can face in the coming years.

Under ‘Interconnections’, investors can gain insight into the complex and unexpected interconnections between today’s global risks, and how they can compound damages for infrastructure assets.

Taken from around the world, the case studies on this page illustrate both the cascading manner in which risks can indirectly come together to impact infrastructure, as well as the way discrete infrastructure-related risk events can trigger adjacent risks for the infrastructure sector and beyond

Risk profiles

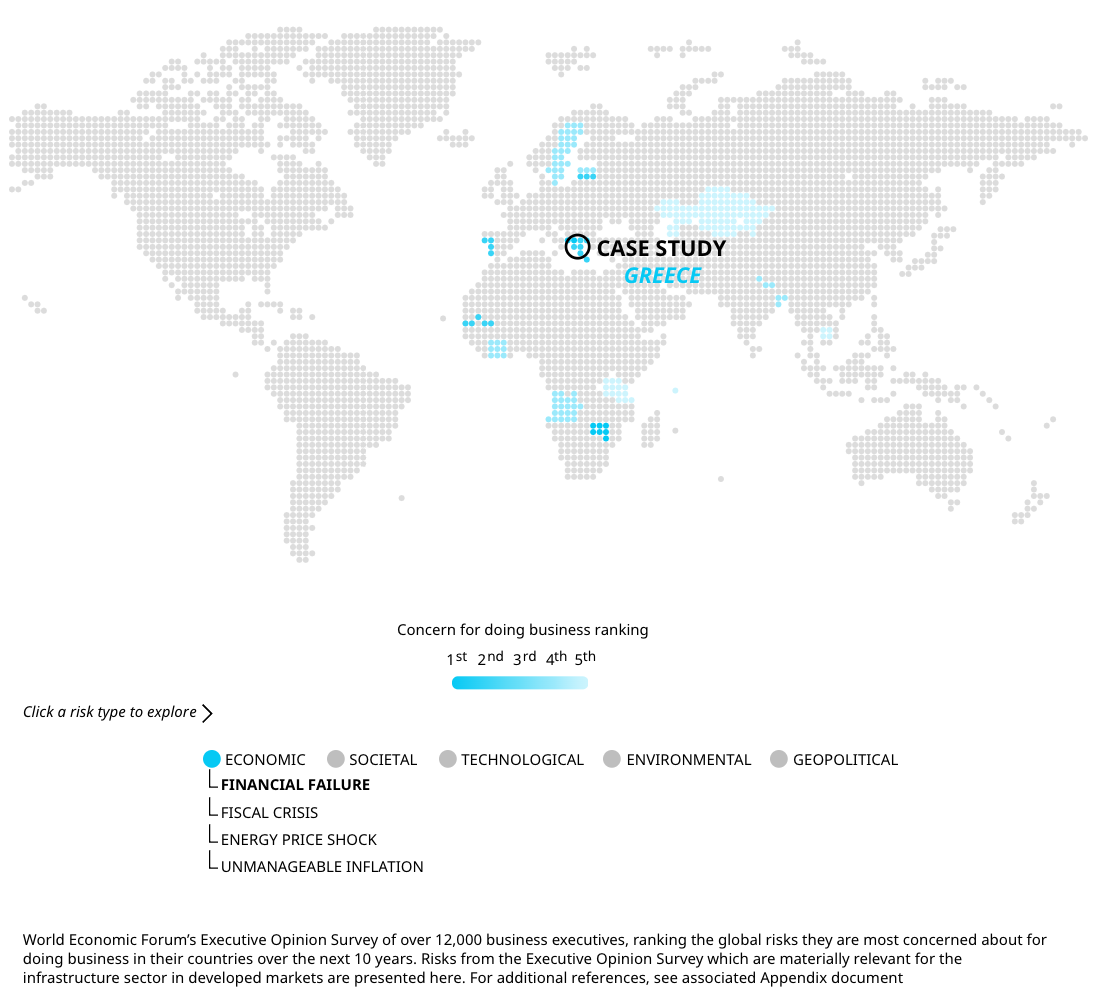

Economic

Financial failure

Case study

Despite being on the road to recovery since the Greek Debt Crisis that arose after 2008, Greece’s four systemic banks still face financial pains. As of Q3 2019, Greece has the highest Non-Performing Loan ratio in the EU at 37.4% (the EU’s overall NPL ratio is 3%). Although some of their ratings have recently been adjusted upwards, many of Greece’s four systemic banks’ products continue to be rated below investment-grade (as of January 2020). The infrastructure sector has already suffered fallouts from instability in the Greek financial system. The post-debt crisis period saw Greek banks on the verge of collapse, with ATM withdrawals restricted to €60 per person per day. Starved of financing, Greece’s largest construction companies suffered a 33% drop in share prices, and infrastructure investment fell by almost 30% between 2009-2013. Today, Greece’s newly inaugurated Hercules plan, which allows the state to guarantee a portion of securitized NPLs, will aid in relieving strains on Greek banks’ loan books and restoring confidence. However, despite a recent upswing in sentiment, infrastructure investors will need to remain vigilant against financial instability as the system broadly remains at risk.

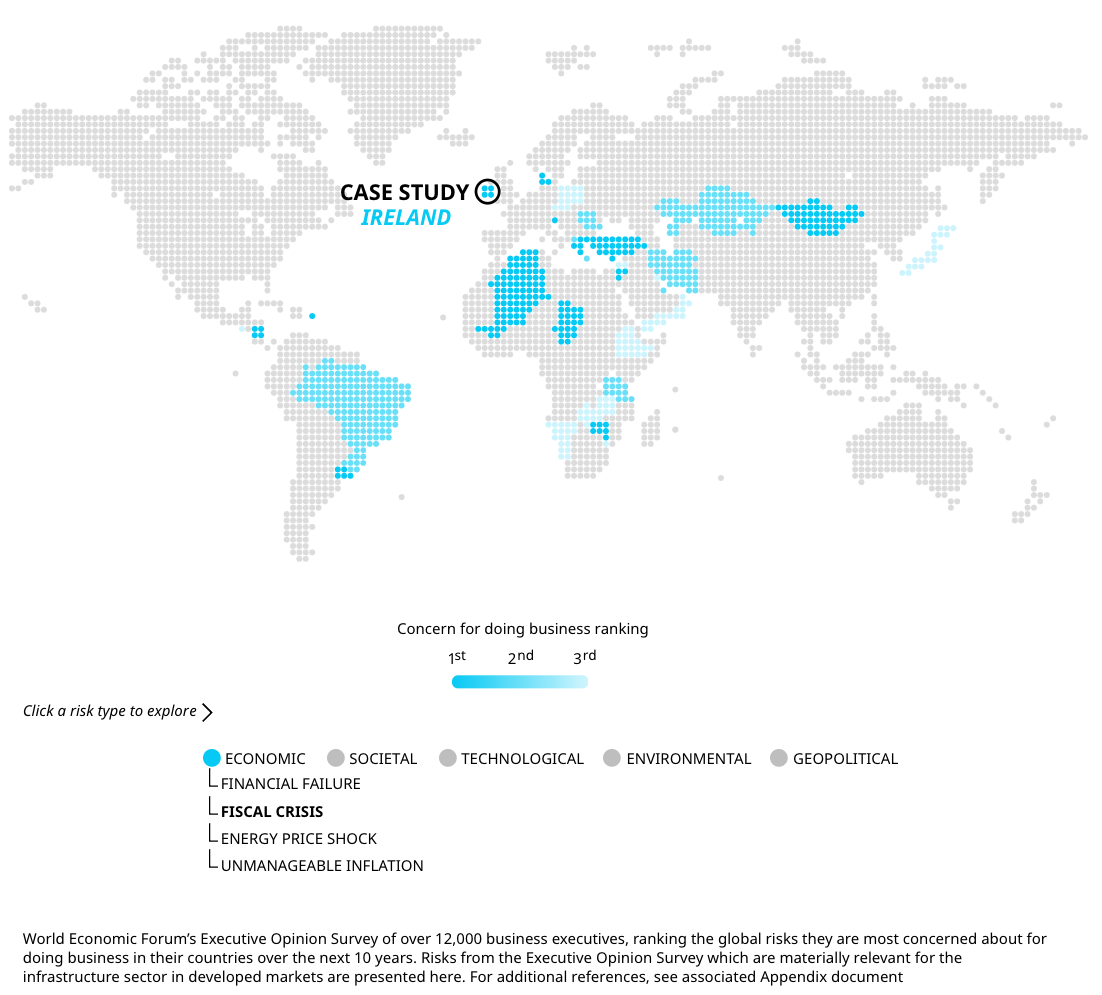

Fiscal crisis

Case study

With over €200 billion in national debt (as of January 2020), Ireland is one of the most indebted nations in the developed world. Despite its restricted borrowing position, the island nation intends to boost infrastructure spending to plug its serious gap in transportation infrastructure, which The WEF’s Global Competitiveness Index ranks considerably below that of Ireland’s regional peers. Ireland’s spending plans could impose additional strains on the government’s fiscal position – slowing its rate of repayment and increasing the risk of financial complication in infrastructure projects. It will be crucial for Ireland to prevent repeating the errors that led to the Portuguese fiscal crisis of the early 2010’s, where Portugal’s overburdened public obligations to infrastructure projects both exacerbated the nation’s fiscal crisis and backfired onto infrastructure investors. At the height of the crisis, the Portuguese government was compelled to renegotiate a cut in its payment obligations for nine major motorway projects owned by both Portuguese and international construction firms. Adequate debt and financial system management will be crucial for preserving the stability of Ireland’s infrastructure sector.

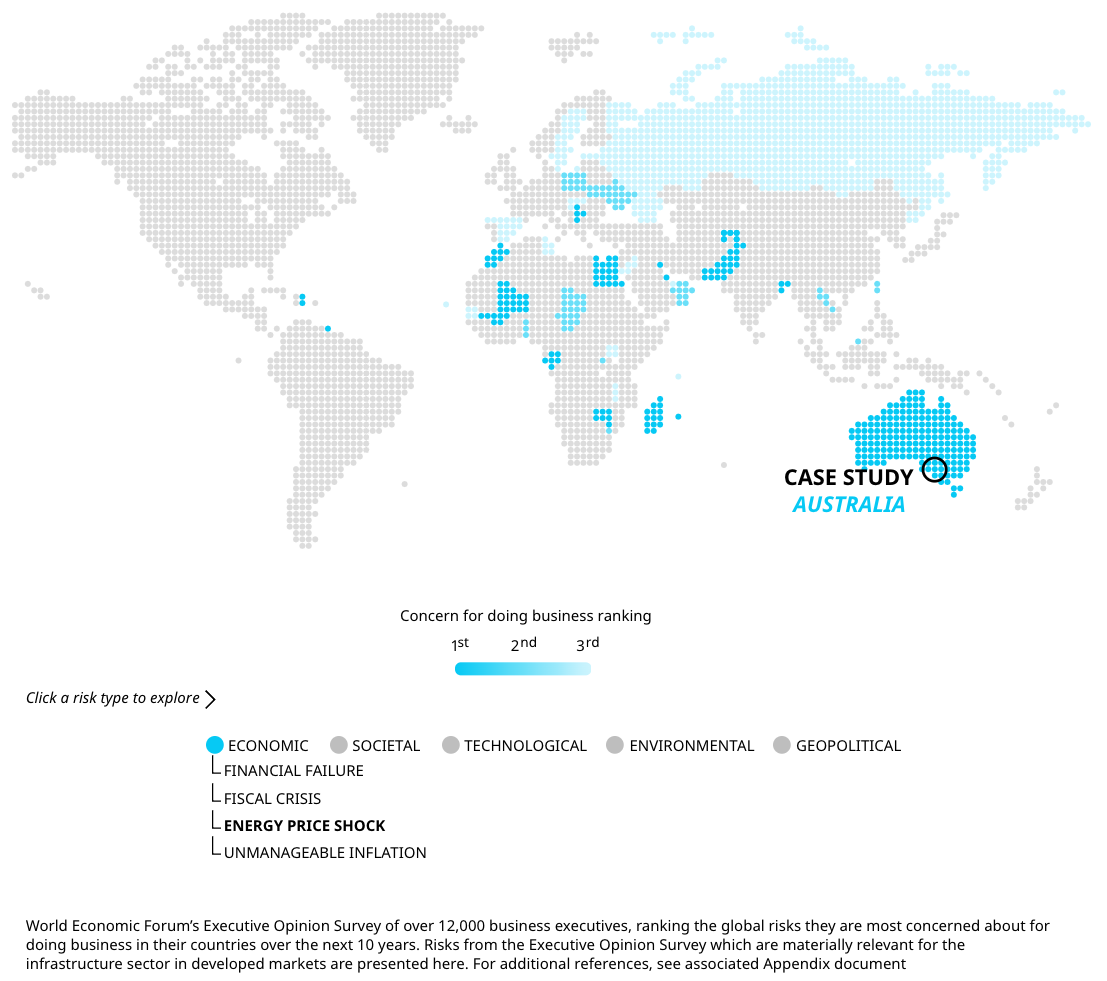

Energy price shock

Case study

Severe energy price hikes in Australia have limited growth in the infrastructure sector, where volatile energy prices have affected long-term contracts and threatened project bankability. Research out of the University of Sydney shows that by 2018, Australian energy prices in real terms had increased by 70% on average since 2008 – making it one of the world’s most expensive markets for energy. This steady rise has also been punctuated by discrete shocks that have shaved off revenue and stalled investment. For example, Telstra, one of Australia’s largest telecoms companies, lost AUD$200 million between 2017-2018 to energy price hikes. These shocks have posed an unexpected obstacle to the company’s plans to cut costs and focus on developing a new 5G network. Although significant recent advances in renewable energy development are projected to bring household electricity prices down between 2019-2022, the Australian energy market is still subject to shocks. Without adequate energy market reform and a revaluation of the country’s approach to implementing its energy transition, energy price shocks could continue to pose obstacles for energy-intensive infrastructure assets.

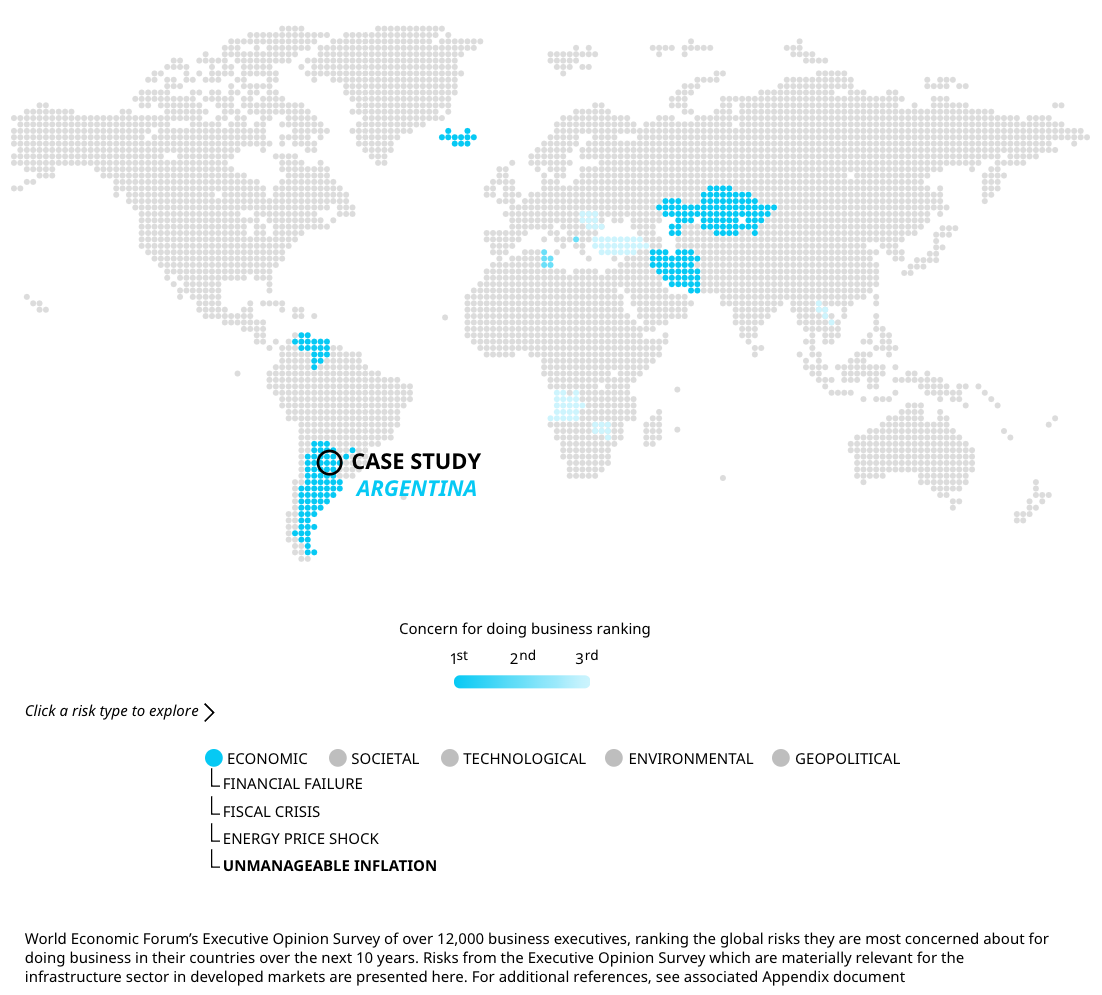

Unmanageable inflation

Case study

When President Mauricio Macri took power in 2015, his government sought to close Argentina’s fiscal deficit and control runaway prices. However, by the end of 2019 Argentina’s year-on-year inflation rate had reached 54%, up from the 30%-40% (estimated) Macri inherited when he took power. Although infrastructure investments can often serve as a safe haven against inflationary risk, greenfield projects – such as those in the renewable energy sector – can struggle to obtain financing in inflationary environments. Argentina’s vaunted green energy projects now face significant financing challenges and delays. Vecaso solar park, a US$90 million 115 MW project in Argentina’s Mendoza province that was scheduled to begin construction before the end of 2019, has been forced to delay construction due to the uncertainties surrounding Argentina’s inflationary economy. Construction on four major wind farms by Argentine energy firm Genneia representing 200 MW were also disrupted for several weeks at the end of 2019 when the associated development banks and export credit agencies stopped making disbursements in the face of climbing inflation.

Societal

Failure of urban planning

Case study

Hong Kong’s hilly and land-scarce geography poses challenges to urban development – particularly in developing more urban transportation infrastructure. Urban planning obstacles in the major Asian financial hub of Hong Kong have contributed to a chronic problem of severe traffic congestion. In a 2014 report from the city’s Transport Advisory Committee, the Committee noted that the expected rate of road length increase up to 2020 would only reach about 0.4% per annum – despite the fact that the vehicle fleet was projected to grow at 3.4% in the same period. This stagnation in Hong Kong’s urban planning policies limits road growth and construction opportunities for developers and investors, despite the clear imperative that exists to alleviate the city’s congestion.

Social instability

Case study

The final months of 2019 witnessed a new wave of social unrest and often violent protests in Catalonia. The unrest was first precipitated in 2017 by the disputed Catalan independence referendum, whose rejection by the central government sparked a general strike and demonstrations across Catalonia. Certain factions of the pro-independence movement have since actively targeted existing infrastructure assets, including but not limited to roads, rail, electricity grids and major transportation hubs such as railway stations and Barcelona’s El Prat International Airport. The Spanish Transport Association estimated a loss of €100 million in just the first week of protests when they re-erupted in October 2019. Another transport industry association, the Spanish Confederation of Goods Transport by Road (CETM), projected that the rising incidence of roadblocks could reach a cost of €25 million euros a day. Madrid continues to struggle – as it has since 2017 – to find a lasting compromise that can both satisfy the pro-independence movement as well as stabilize the Catalan region.

Water crises

Case study

The scarcely-resourced island nation of Singapore faces considerable water shortage threats. The city-state is dependent on imports for approximately 40% of its water supply, and the local water authority projects that Singapore’s total water demand could double by 2060. As climate change continues to render ecological patterns less and less predictable, the threat of water shortages continues to grow. In July 2019, Singapore experienced its first dry spell in five years. This resulted not only in decreased water levels in Singapore’s own catchment areas, but also in the nearby Linggiu Reservoir in Johor Bahru, Malaysia: a major water source for the city-state of 5.8 million people, from which Singapore is contractually permitted to extract some 250 million gallons of water per day. As a result of the water shortages in the region, the Singapore government has been forced to raise water prices in recent years, introducing potential reputational and competition risks for the city’s water utility operator.

Technological

Adverse technological advances¹

Case study

The emergence of big data has given rise to concerns around data privacy, unconsented data collection and potential misuse. In 2017, the central German government passed a series of new surveillance and security laws that were widely considered to be the most wide-reaching and intrusive of their kind in Germany. These included new laws that required telecommunications providers in Germany to collect and retain user data, that created legal basis for state police to use malware to spy on Internet users, that allowed greater video surveillance in public infrastructure, and that required airlines to collect passenger information. These new laws did not emerge without backlash: one of these laws has already been deemed a violation of EU law, and the others continue to face judicial or media scrutiny. For infrastructure investors, the main risk will arise from reputational damage and litigative actions – their assets could potentially be entangled in public protest or lawsuits alleging breach of privacy or data abuse.

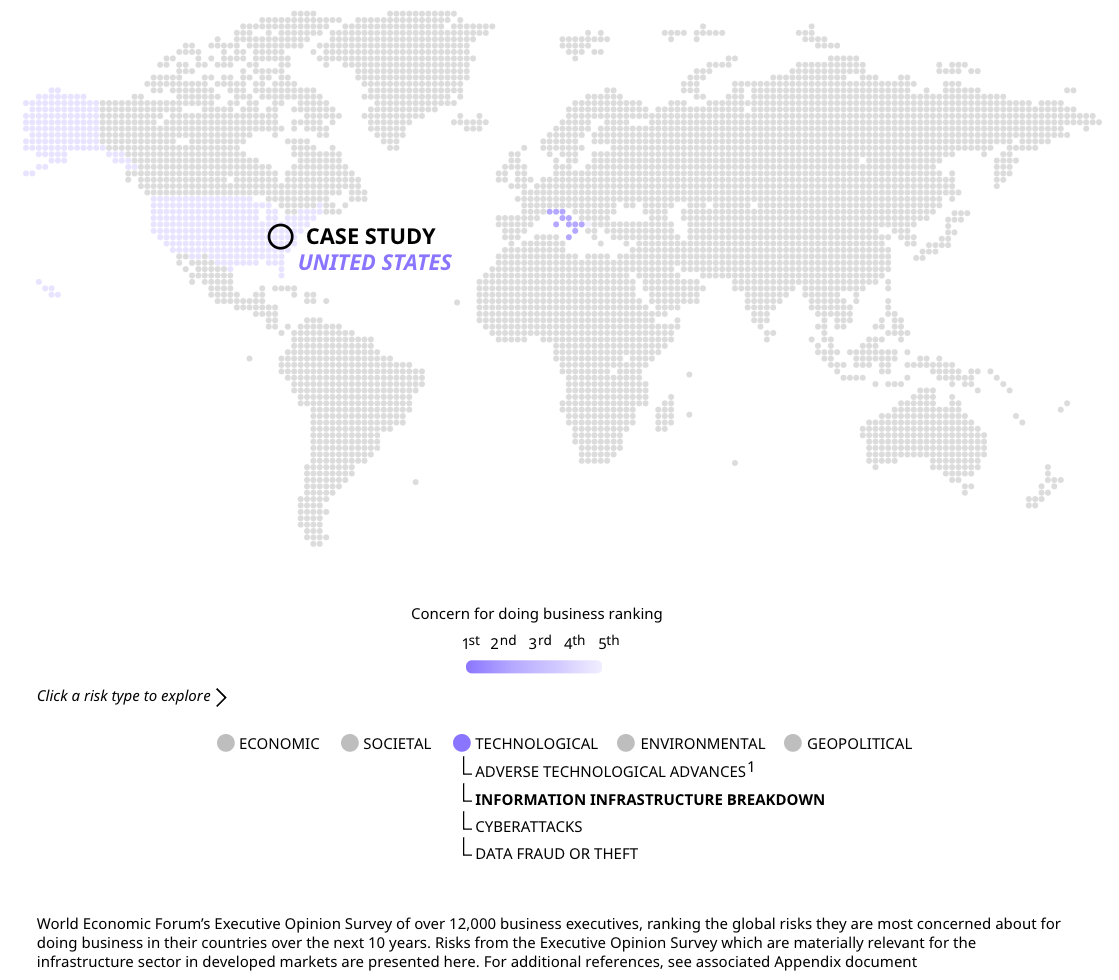

Information infrastructure breakdown

Case study

The United States’ internet network has suffered a number of severe outages in recent years. In June 2019, major internet infrastructure and cybersecurity service Cloudfare suffered an hours-long outage and lost 15% of its global traffic. A similar incident occurred in November 2017, when Level 3, another internet infrastructure service provider, experienced disruptions to its service – resulting in an unusually large internet outage that lasted approximately 90 minutes. These incidents have had significant repercussions for telecommunications companies. In the case of the Cloudfare outage, Cloudfare quickly pointed to its network provider as the primary cause of the disruption. In the Level 3 case, several major Internet Service Providers (ISPs) found their internet connections failing across the United States – including those of the nation’s biggest telecommunications giants. Telecommunications providers can indeed find themselves at the receiving end of both disruption and blame in the events of information infrastructure breakdowns, making it all-the-more necessary that they remain resilient to these incidents and work with authorities to address their root causes.

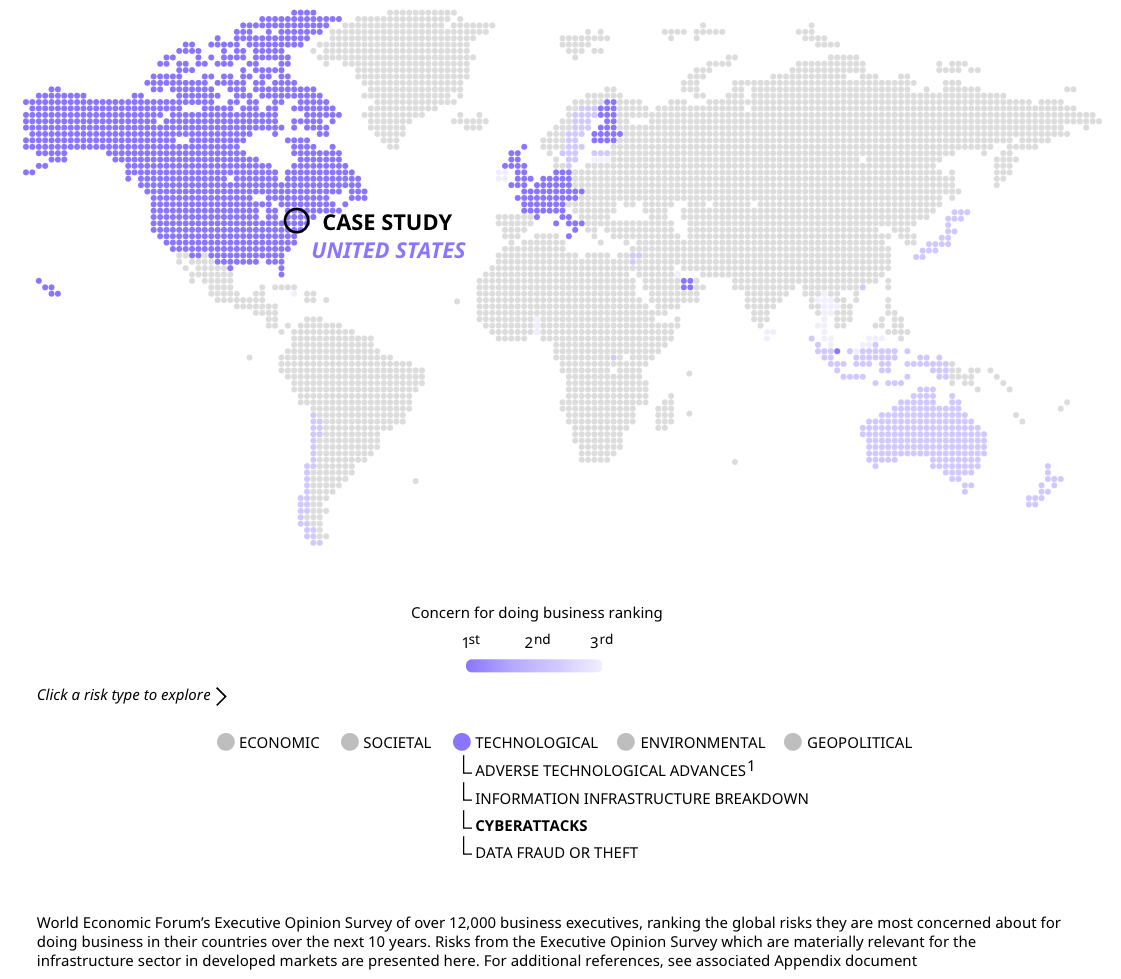

Cyberattacks

Case study

Government intelligence out of the United States indicates that beyond the often highly-profiled energy sector, the country’s water and wastewater sector is also under direct and serious threat. In 2018, for example, a water utility based out of North Carolina reported that it had sustained “a sophisticated ransomware attack” on its computer systems. Although the safety of the company’s water supply and customer information was not compromised, the attack wiped out several of the Onslow Water and Sewer Authority’s other databases – forcing them to rebuild the affected systems from the ground-up. In response to growing cyber threats, the sector has now also come under additional regulatory scrutiny. In 2018 the US Congress passed America's Water Infrastructure Act, requiring any water utility serving more than 3,300 people to carry out a "risk and resilience" assessment of its networks, including a review of cyber defences. With utility systems in the US increasingly under threat of cyberattack, water systems operators and investors will need to stay agile to be able to recover from attacks and adapt to new policies and regulations.

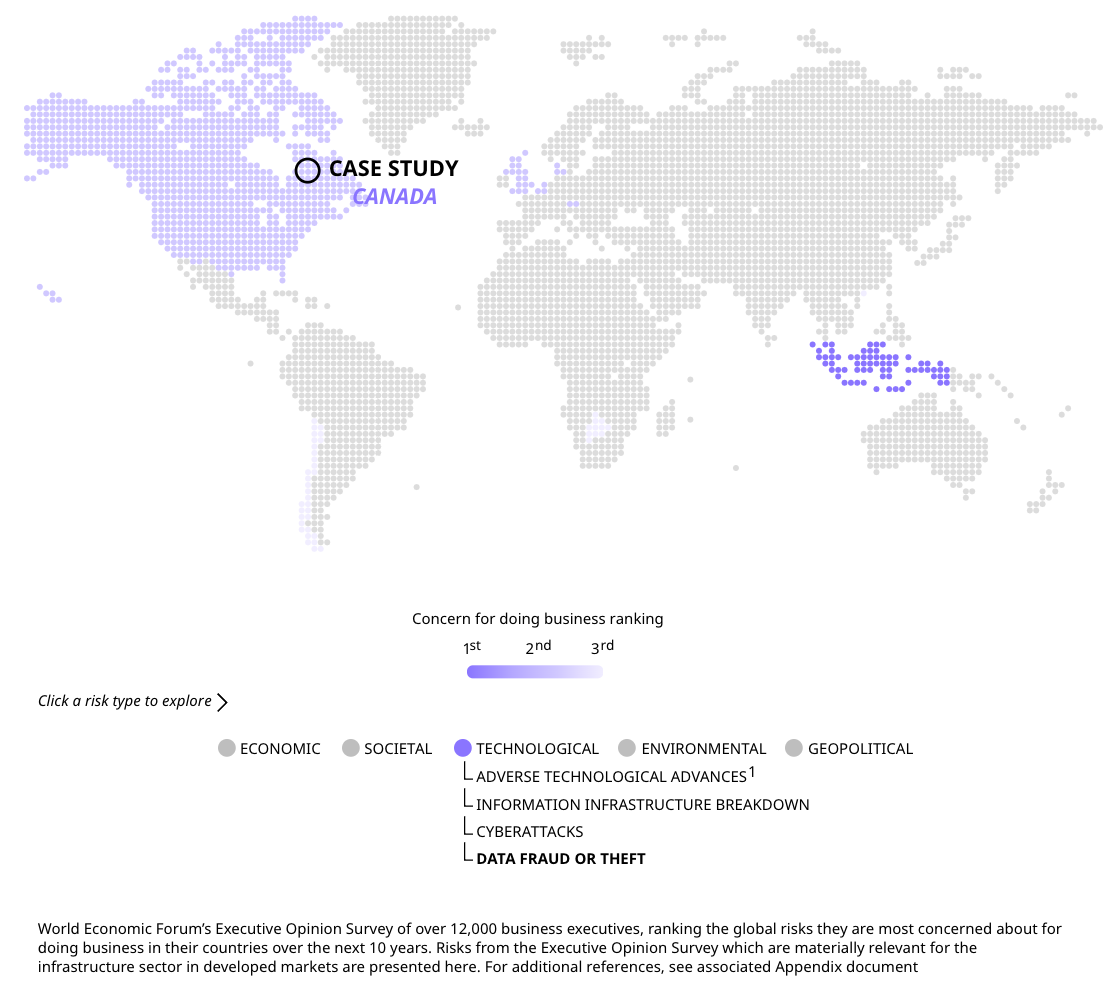

Data fraud or theft

According to the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, the country’s federal data privacy watchdog, more than 28 million Canadians were affected by a data breach in 2019. Reports of data theft have increased dramatically since the government introduced mandatory data breach reporting law for Canadian businesses in 2018. One such breach occurred on 17 April 2019 with significant fallouts for a major infrastructure sector player when a large Canadian telecommunications provider revealed that sensitive information belonging to 15,000 of its customers was breached. Researchers say that the cascading effects of the breach mean that approximately 5 million records were exposed. Unencrypted data such as credit numbers, security codes and credit scores were among some of the data types affected. The incident placed the company’s brand reputation and trust in jeopardy, and raised the company’s potential risk of legal and regulatory repercussions.

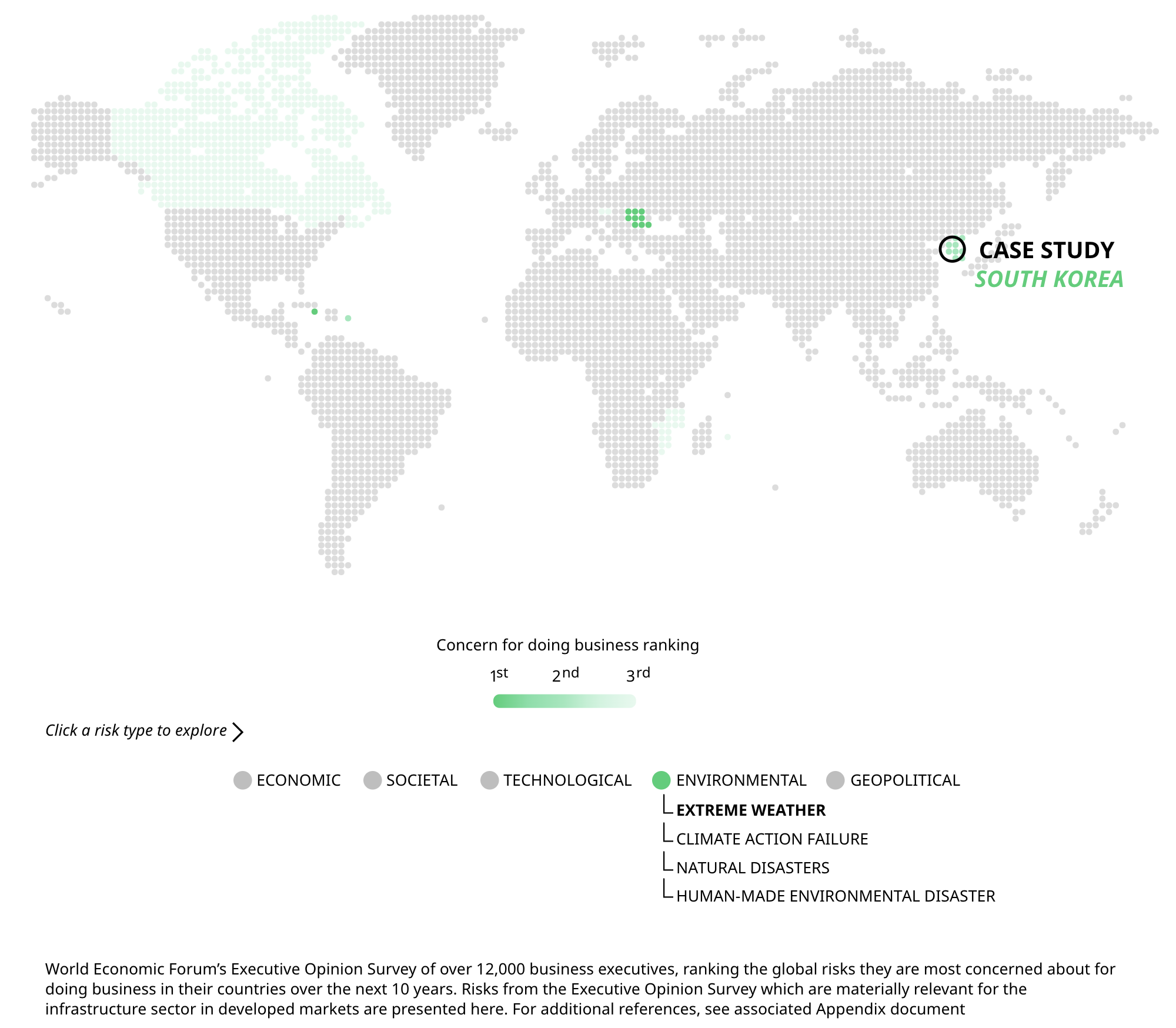

Environmental

Extreme weather

Case study

South Korean infrastructure suffered multiple instances of damage from major tropical storms in 2019. In September, Typhoon Lingling resulted in more than 120 flights being grounded nationwide, as well as the disruption of a commuter rail network and closure of a key gateway bridge to a major airport. Two weeks later, Typhoon Tapah damaged utility infrastructure, cutting power supply to 27,790 houses, while simultaneously causing the cancellation of 250 flights in 11 airports across Korea. Tapah also caused serious flooding across 60 roads in the southern region, with both public and private facilities reporting approximately 600 cases of damage – particularly to an ongoing seawall project in Ulsan. In October, tropical storm Mitag made landfall, bringing 500mm of rainfall to the south, causing widespread flooding and power outages to more than 44,000 homes. A 2017 study says that when the maximum potential annual damage costs from natural disasters are considered, private facilities could represent almost a quarter of the projected US$20.9 billion in damage through 2060 in South Korea.

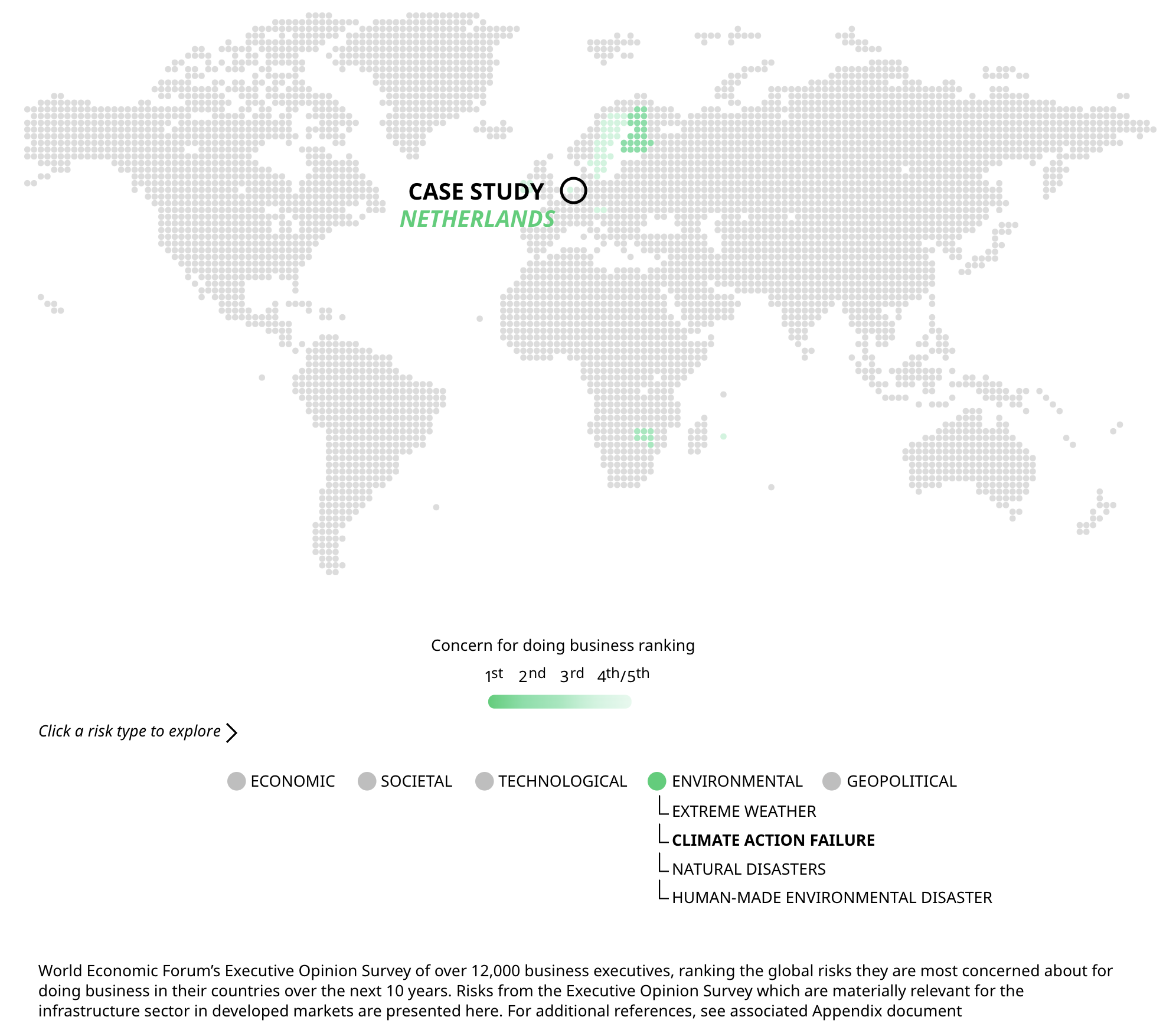

Climate action failure

Case study

The Netherlands is a global pioneer in adopting innovative infrastructural adaptations to mitigate the negative impacts of climate change, and is compelled to do so because of its intrinsic geographical challenges. Roughly a third of the country lies below sea level and continues to sink further, making it one of the most vulnerable nations to climate change. In November 2018, the Dutch government pledged to invest €600 million in climate adaptation innovations, on top of the existing €1.3 billion a year on the Delta Plan, which focuses on limiting the probability of flooding through construction of public infrastructure such as dikes, beach nourishment and storm surge barriers. However, despite its achievements, the Dutch government still has room to shore up its coastal defences. Although major Dutch urban centres face flood risk of 1/10,000, in the northern and southwestern sub-sea level coastlines – where the major port city Rotterdam sits – the risk of dikes breaking from storm surges rises dramatically to 1/4,000, and even 1/1,250. Exacerbated by rising sea levels, risk factors could increase tenfold – up to 1/125. Failure to adapt to these increasing risks could have major impacts on Dutch infrastructure: 90% of the urban infrastructure in Rotterdam sits below sea level, for example.

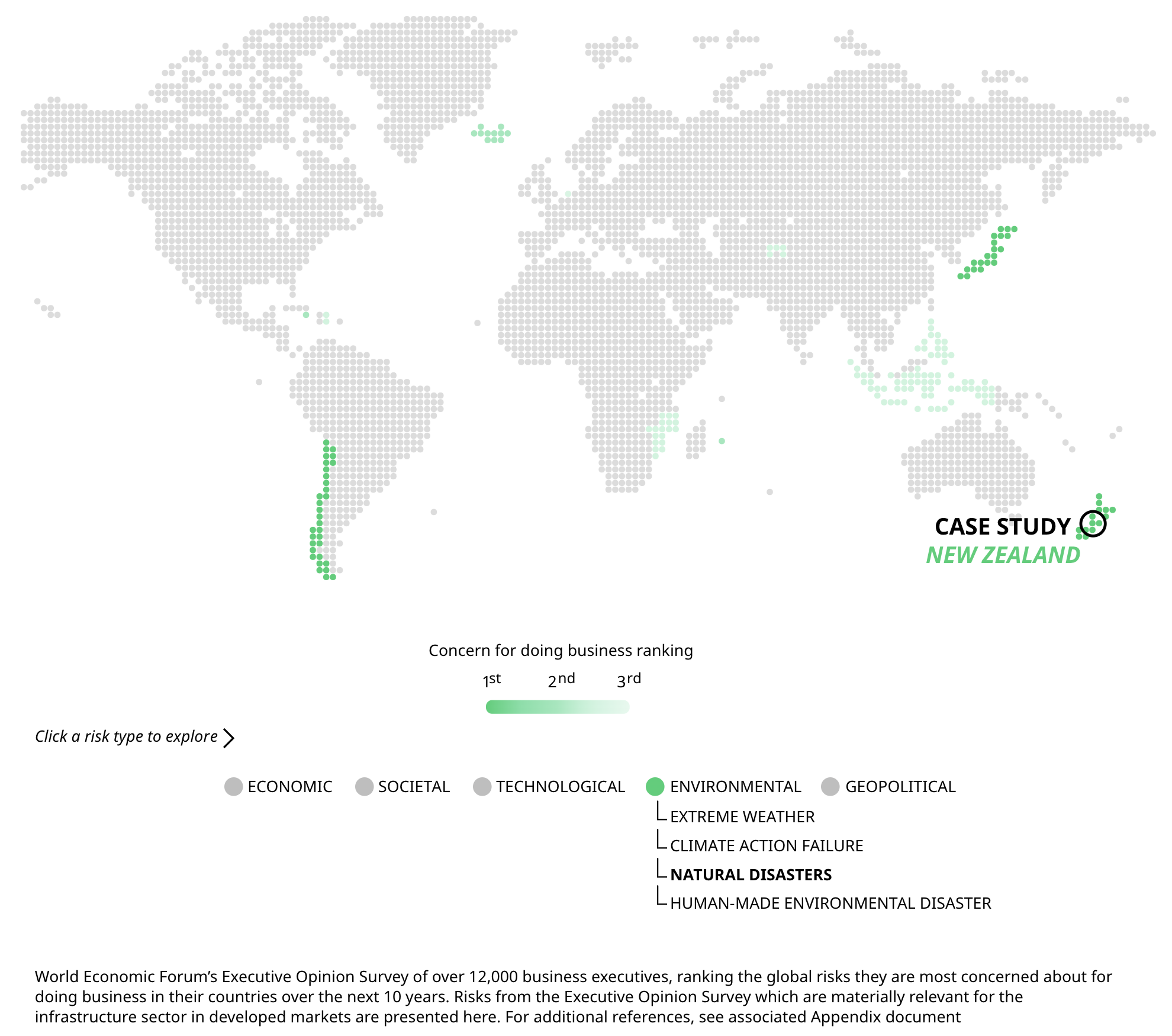

Natural disasters

Case study

The 7.8 magnitude Kaikoura earthquake devastated New Zealand in 2016. The earthquake severely damaged infrastructure across the country, including roads, railways and ports, triggering additional side effects such as landslides and tsunamis. The post-disaster damage came to businesses in the form of both insurance claims and lost revenue. Over NZD$1.8 billion in insurance claims were reported after the incident, out of which NZD$1.4 billion originated from the commercial sector according to the Insurance Council. In the Kaikoura region – the epicentre of the earthquake – the utility, construction and transportation sectors lost 34% of their operability (i.e. of their normal productive capacity) within the first week of the disaster. New Zealand, which lies on a seismically active zone along the Pacific Ring of Fire, continues to be at risk of earthquakes and other associated natural disasters – and infrastructure is at the forefront of such risks.

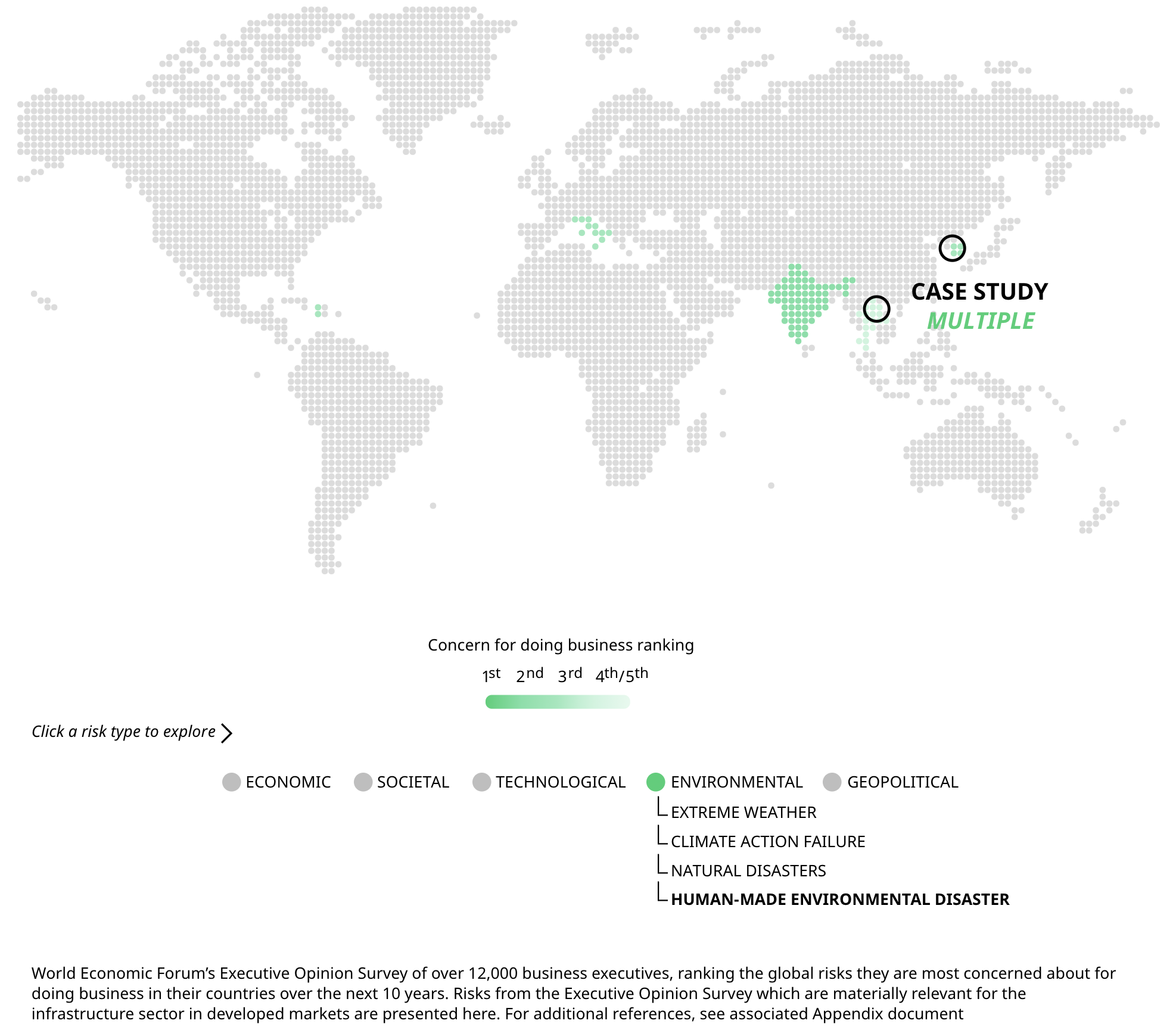

Human-made environmental disasters

In July 2018, the Xe Pian-Xe Namnoy dam in Laos’s Champasak province collapsed, flooding downstream villages, displacing at least 6,000 people. The project, part of a regional US$1 billion dam system, was jointly funded and developed by two private Laotian entities and two South Korean companies. Shortly after the disaster, the Lao Ministry of Energy and Mines released statements on construction standards and accelerated project timelines as potential causes. Other independent analyses have also identified dam design and material selection as plausible contributing factors. In response, both of the Korean companies involved committed a combined US$11 million in relief efforts. They also suffered significant financial hits, with one company seeing a 30% plunge in stock prices. Social backlash additionally posed potential reputational regulatory and legal risks for relevant stakeholders, as Korean civil society groups implored their government to disclose information and conduct independent investigations.

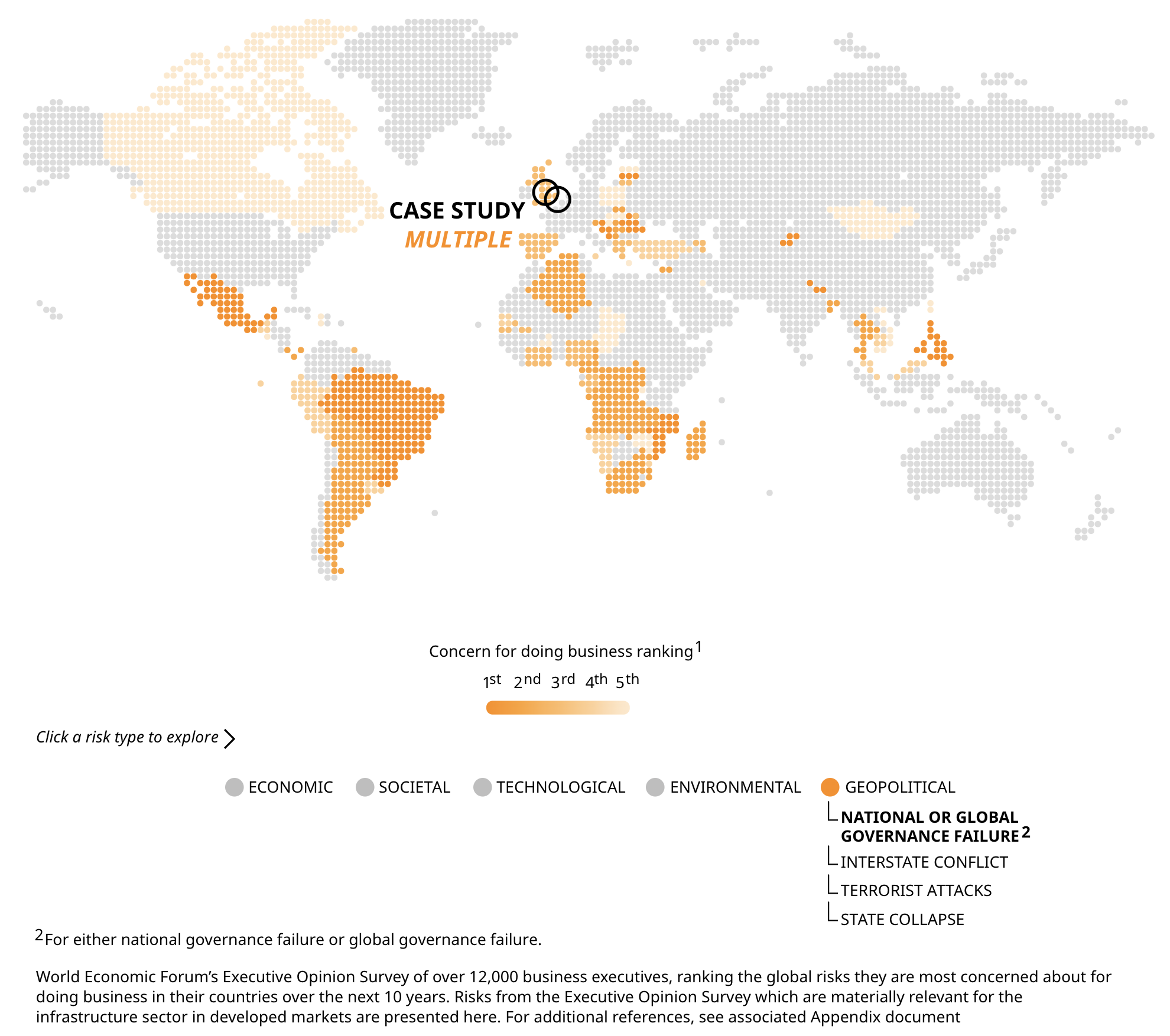

Geopolitical

National or global governance failure²

Case study

The inability of national, regional, and global governance entities to resolve political differences will have serious impacts on the infrastructure sector. National and regional governance uncertainties can give rise to delays, cancellations, financing shortages or contract renegotiations for greenfield projects. The ambiguity in the lead-up to the finalization of a Brexit deal between the EU and the UK, for example, introduced new uncertainties and delays for two major infrastructure projects: a £2 billion tunnel beneath Stonehenge and a high speed rail link between London and Birmingham called the HS2. Brownfield projects will also face significant fallouts. In particular, regional governance uncertainty can severely undermine revenue growth potential for assets sensitive to trade and passenger flows (such as transport) or that provide cross-border services (such as cross-border energy or water infrastructure). Canadian railways, for example, source 30% of their revenues from trade. As law firm Norton Rose Fulbright has noted, the newly minted USMCA trade agreement between Canada, the USA and Mexico, leaves several important questions unresolved for these Canadian railway operators – particularly around procurement, disputes, and tariffs.

Interstate conflict

Case study

Today’s geopolitical climate means that interstate conflict has the potential to turn ‘hot’, i.e. to lead to actual military confrontation. These developments can result in severe physical damage to infrastructure assets exposed to battle zones, as well as revenue loss or process disruption from blockades or occupation. Interstate conflicts can also manifest as economic tensions that bite into revenues for trade-dependent or cross-border infrastructure assets (see Canada example), or that limit foreign investment into local infrastructure. A trade war between Korea and Japan that began in 2019 has resulted in the active avoidance of Japan-Korea investment flows due to souring relations, for example. In July 2019, major institutional investor Korea Teachers’ Credit Union (KTCI) scrapped plans to invest over US$70 million in a global infrastructure fund packaged by a major Japanese trading house due to escalating tensions. Diplomatic dialogue will be crucial to restoring trade and investment flows between these two major Asian economies.

Terrorist attacks

Case study

Transportation systems are the world’s most heavily-targeted infrastructure sector for terrorist attacks according to the Global Terrorism Database. Between 2000 and 2018, transportation systems faced higher numbers of terror attacks than water systems, utilities, telecommunications, or airports and aircraft systems globally. The United Kingdom is no exception: the country’s transportation system saw 28 terror attacks in this period, compared with 8 terror attacks on all other forms of infrastructure combined. The destabilizing effects of frequent terror attacks have had particularly important impacts on London’s underground railway system. Research shows that after the 7/7 bombings across London’s public transport systems in 2005, passenger journeys on the London Underground fell by an average of 8.3% for the following 4 months. In 2017, passenger numbers fell in 2017 for the first time in 20 years – in part, the railway operator and experts concluded, due to fears of terror. Transport for London (or TfL)’s spending programs on safety and collaboration with authorities will be instrumental in protecting against losses to human life and restoring the public’s confidence in this critical infrastructure system.

State collapse

Civil conflict between the Mexican government and organized crime organizations threatens the stability of the state. Estimates say that since hostilities began in 2006, approximately 150,000 homicides have occurred as a result of organized crime -- denoting, by political science definitions, that the country is in a state of war. The conflict has had particularly significant impacts on port assets in Mexico. In August 2019, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (or ‘AMLO’) acknowledged that organized crime rings were in control of several customs stations and ports, highlighting the port of Manzanillo – Mexico’s largest port by cargo throughput – as one of the country’s ‘most infiltrated’ points. AMLO has announced his intention to push for shifting control over the country’s ports from the Secretary of Communications and Transportation (a civil body) to the Secretary of the Navy (or ‘Semar’, a military body). The prospect of being constrained by conditions imposed by the Semar has raised concerns of business disruption and increased costs amongst both port service operators and the President of the Port Maritime Council of Mexico.

Interconnections

Case study

The Indian city of Chennai frequently suffers damage from extreme weather: particularly from severe water shortages as well as unmanageable flooding. This has been attributed in part to uncontrolled urban growth after the city began to actively attract IT-sector companies and talent in 2008, resulting in significant encroachment onto the city’s water bodies and natural drainage systems. This failure of urban planning and of climate-change mitigation and adaptation has increased the damage the city sustains when extreme weather strikes. Chennai’s local government has also been slow to curb the power of the city’s local “water mafias”, who charge extortive water prices in difficult times. This failure of national governance has also been raised as a factor behind the government’s inaction over infrastructure development and resilience-building against extreme weather.

As a result, in 2015, when the city was inundated by its heaviest rainfall in over 100 years, over a million residents were displaced from their homes and the city was disrupted for days. In 2018 Chennai’s rainfall fell by 55%, leaving the city without rainfall for 200 days and scrambling for water supplies. These water crises and the failure of the city’s critical infrastructure to manage them have occurred recurrently in recent years, and have also affected infrastructure operators across sectors. Major power distributor Tangedco lost nearly US$140 million each year between 2015-2018 due to flood damages, and in 2017, the major 1050MW Tuticorin thermal plant was temporarily shut down due to a lack of water for cooling. Additionally, Chennai’s water shortages in 2018 caused companies across industries to pay as much as 30% more for private water supplies.

Case study

Social instability – fueled in part by involuntary migration from neighboring regions – has given rise to populist governments in several Eastern European nations such as Poland and Hungary. Several of these new governments have expressed hesitation over the implementation of climate change mitigation and adaptation measures, despite EU targets requiring considerable climate commitments from member nations.

As a result of this failure of the regional EU governing body to encourage member nations to comply with its targets, renewable energy investing in these countries can be risky. Poland’s energy policy in particular has been described by industry members as a ‘rollercoaster’. The country’s wind sector has faced a range of recent policy shocks, from far-reaching construction limitations to plans for caps on green certificates and renewable energy prices. In 2018, a major US renewable energy group launched international arbitration proceedings against the Polish government, claiming the EU country had reneged on its commitments to build wind farms through its new policies. The firm now stands to lose considerable revenue from Poland’s failure to invest in critical infrastructure. The firm will also need to bear legal fees, as well as operational costs of exiting Poland, where it says it will no longer be doing business.

Case study

In 2011, three nuclear cores at the now-famous Fukushima Daiichi power plant in Japan melted when a 14-meters high tsunami, triggered by a magnitude 9.1 earthquake, inundated the plant. This natural disaster and the subsequent failure of the critical Fukushima power plant resulted in the involuntary evacuation of 100,000 people, and contaminated food and water resources in the prefecture – giving rise to lawsuits against the company responsible and pressures on other surrounding infrastructure companies reliant on stable populations and water resources..

Japan still feels the impact of Fukushima today. By 2012, the government had moved quickly to enact the sweeping denuclearization of the Japanese energy sector. The policy reform meant the loss of 30% of the country’s energy-generating capacity, and thus increased reliance on oil and gas imports, exposing the Japanese economy to external energy price shocks. The financial burden on the Japanese government has also been significant: a 2019 estimate forecasts that the government could take on over US$560 billion in recovery costs over the next 40 years. Currently facing the world’s highest general government debt burden, the Japanese government’s fiscal position faces additional strains from the fallout from Fukushima.

Case study

In March 2016, Verizon’s monthly security breach publication drew widespread attention to a cyberattack on a major unnamed water utility. The hack was suspected to have been administered by a “hacktivist” group with motivations relating to the ongoing inter-state conflict in Syria. The system in question ran on operating systems from over a decade prior, leaving it particularly vulnerable to such an attack.

The attack gave rise to a number of related risks for the anonymous company. The compromised system allowed the hackers to take control of the utility’s water flow and chemical treatment system. Although the company was able to identify and reverse the chemical and flow changes in time, this critical infrastructure failure could have caused widespread health damages to the local community by distributing badly treated water, raising risks of infectious disease and water crises. The hackers additionally gained access to over 2.5 million personal and financial records, giving rise to data fraud risks.

-

A closer look at the impact of climate-induced physical and transition risks for the infrastructure sector, and viable mitigation solutions and strategic opportunities for investors

Find out more

A closer look at the impact of climate-induced physical and transition risks for the infrastructure sector, and viable mitigation solutions and strategic opportunities for investors

Find out more

-

A focused overview of the ways in which transformative technologies are changing the infrastructure sector, and pertinent imperatives for investors to stay ahead of the curve and future-proof their assets.

Find out more

A focused overview of the ways in which transformative technologies are changing the infrastructure sector, and pertinent imperatives for investors to stay ahead of the curve and future-proof their assets.

Find out more