The first article in this series outlined the evolving market dynamics creating new opportunities in Care at Home (C@H) programs. In this post, we detail where and how to start thinking about the financial implications of actively shifting care to patients’ homes. In the third article, we offer considerations to ensure a successful launch of C@H.

Starting with Hospital at Home as the foundation

The scope of services that can be provided at home is large and growing. For health systems, whether already offering traditional services like home health or considering their first foray into the home, hospital at home (H@H) presents the most attractive starting point. H@H offers the largest addressable spend of all other care modalities and can provide immediate relief for inpatient capacity issues by decanting volume away from the facility. And there’s an established reimbursement model through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Acute Hospital Care at Home program.

H@H programs include various patient flows with the most common one being an initial emergency department visit followed by hospitalization at the patient’s home. Other models may include transfer to home following several days in the hospital, an initial emergent care at home followed by H@H care, post-surgical recovery at home, and other services with medium- to low-acuity conditions that can be safely treated at home.

Requiring a comprehensive suite of at-home capabilities, including dedicated clinical and non-clinical resources, a robust technology platform, and contracted services, H@H programs can’t be launched overnight. Health systems have to cover most of the upfront costs, including building out or vending technology platforms to reach patient homes and delivering medical supplies, but early adopters like John Hopkins Medicine report savings of up to 30% compared to traditional inpatient care.

Expanding to other Care at Home programs

Once H@H capabilities are built and operable, there is a natural extension into other C@H modalities, including post-acute care, both in terms of care pathways and through leveraging similar resources and capabilities. In fact, a H@H patient can be easily transitioned to a post-acute care at their home using the existing communication and monitoring set-up and they are familiar with how to work with the C@H team. Unfortunately, there is no established payment model yet for H@H in the post-acute space. However, studies have shown that H@H patients have lower rates of readmissions compared to hospital inpatients. And with hospitals subject to payment penalties for readmission rates exceeding 30-day all cause readmissions, the incremental costs of providing transitional post-acute care may be easy to justify financially. On top of that, most markets are experiencing extreme staffing shortages, leading roughly 46% of nursing homes limiting new admissions.

Health systems can take various approaches to building out subsequent modalities based on their strategic needs. Where hospital capacity is challenged, the most logical next step may be to further invest in acute or sub-acute models such as ED or Observation at Home. For systems seeking to enhance their performance on value-based contracts, home-based primary care may offer a strong return. Systems looking for new streams of revenue may find home infusion or home dialysis to be an effective strategy.

Still, health systems should not underestimate the degree to which C@H operations and logistics depart from facility-based care models, and therefore the investment required to build such a foundation. Unlike building another surgical center, hospital wing or urgent care site, C@H programs require new capabilities, operating models, workflows, and technology. Providers are accustomed to centralizing patient care in a physical location and using large-scale, capital intensive equipment and operations to provide care. Operating out of the home means thinking differently about how to serve patients. Consider drug management. Large pharmacies, often situated in hospital basements, send medications to nurses and automated dispensing cabinets at scale. Drugs are then administered by clinicians to patients in a controlled environment. In a C@H environment, these same drugs need to be dispensed on demand, bear consumer-friendly labelling, and be delivered at the right time to the home. The compound is unchanged, but operations are vastly different. All of this requires a new operating model, new assets such as a 24/7 command center, logistics networks, patient and clinician facing technology, and a field workforce.

Building the business case for Care at Home

How can a system justify all the necessary costs for home-based care, yet still realize financial value? Doing so requires contextualizing the necessary investment against the full set of direct, indirect, and longer-term value drivers:

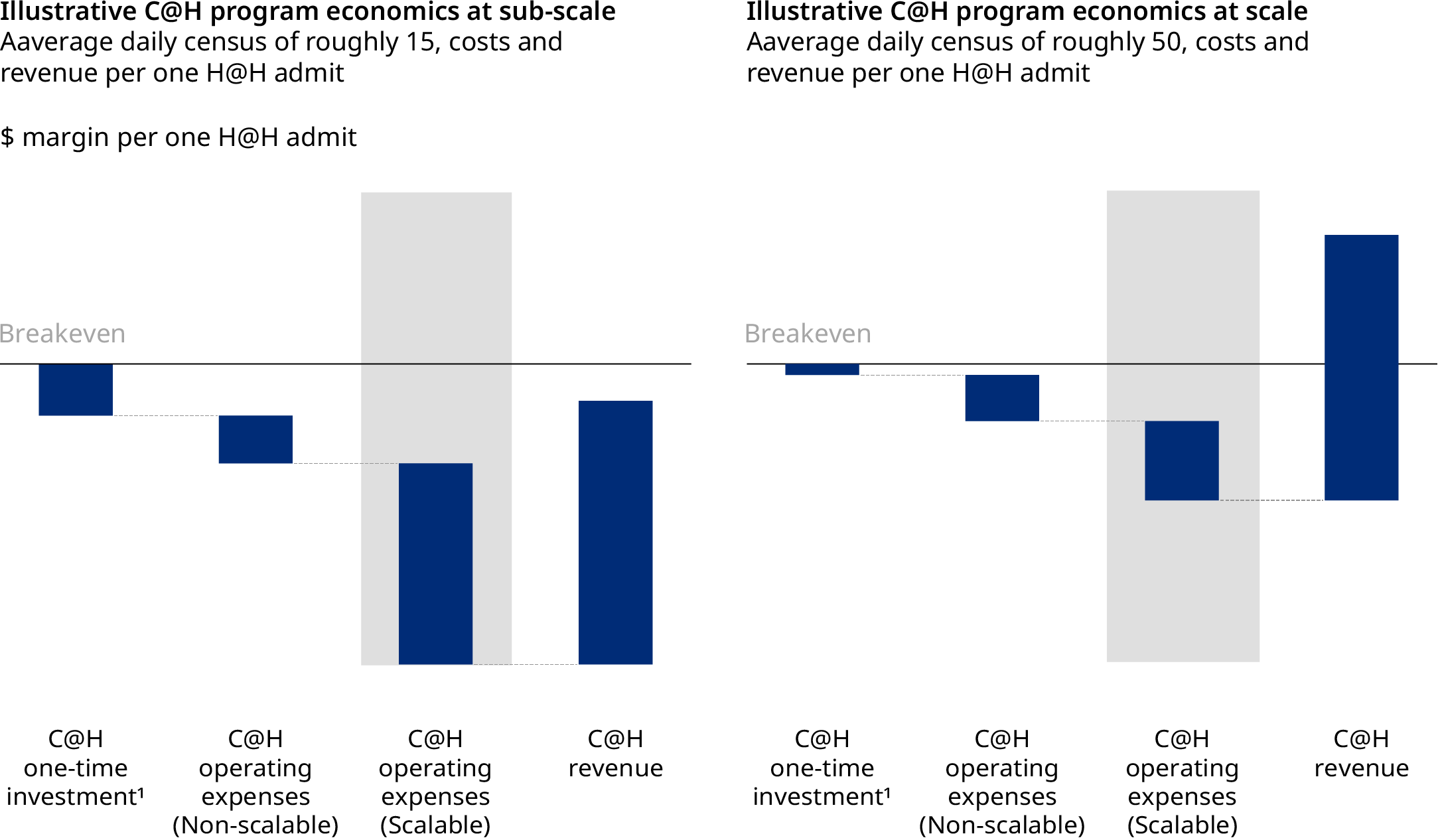

- Direct value comes from the margin generated by the C@H operation itself. Most of the investment and operating costs are sensitive to economies of scale — technology, virtual care, command center, in-home labor, administrative and overhead, vendor contracts. Our analysis suggests that up to 50% of per unit cost can be saved when comparing a sub-scaled and a scaled operation. Thus, scale is the single most important element to achieving financial sustainability in a C@H program. It can be achieved by pulling several levers, including increasing the addressable volume for a modality — more hospitals, more payers, more insurance segments, more conditions/DRGs — gaining clinician buy-in, and implementing multiple modalities of care to leverage capabilities and share costs.

From technology to in-home labor, each element needed to support C@H plays a role in reducing unit costs. The cost per unit of care changes in different rates for different expense categories, as shown in the table below.

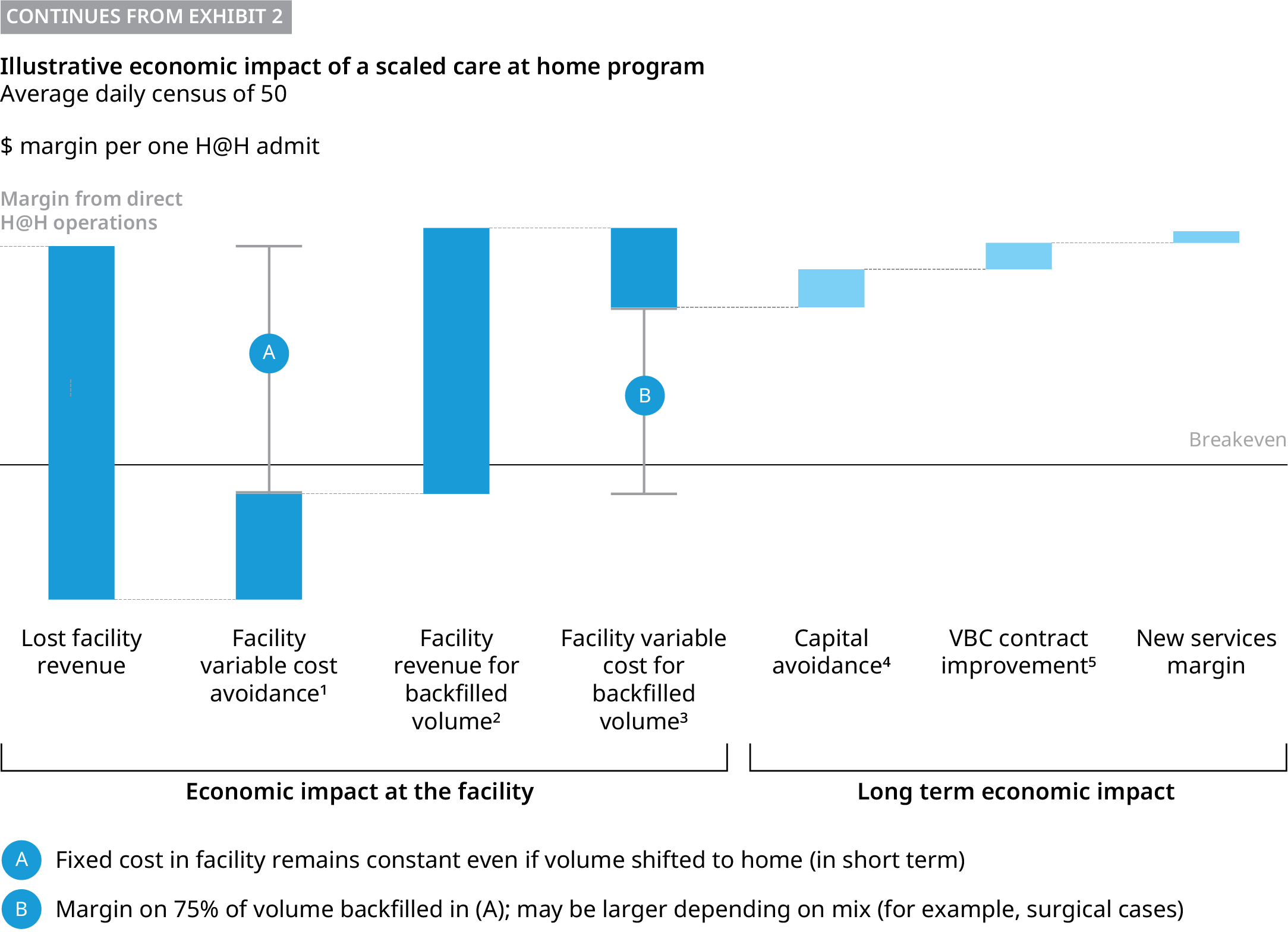

Indirect value is driven by using newly available facility space as volume is shifted to home. Hospitals are largely a fixed cost operation. As admissions are decanted to the home, significant costs remain unchanged, such as building and equipment maintenance. However, if a system can backfill capacity with new volume, ideally with a higher margin case mix such as elective surgeries, it can significantly benefit from any new volume leveraging the already existing cost structure.

- Longer-term value drivers include three potential sub-elements:

- Capital spend avoidance from building or renovating physical capacity once volume can be decanted at scale to the home. With the capital cost of a new acute care bed nearing $2 million, savings can be meaningful.

- Enhanced performance on value-based care, whether by incurring lower cost per admission or improving outcomes – lower complications and re-admissions.

- Margin from new services the system is not providing today such as home dialysis or infusion. Overall, we see the bulk of value potential as being concentrated in the direct and indirect value categories, with the longer-term value drivers category being meaningful yet secondary.

Overall, we see the bulk of value potential as being concentrated in the direct and indirect value categories, with the longer-term value drivers category being meaningful yet secondary.

Although the case to offer C@H is universal from a clinical and patient experience standpoint, the business case may not balance out for all systems. We expect the business case to be resoundingly strong for systems with strong payer partners and in markets with sufficient demand. There are several critical elements to launching the program that warrant special attention, including how to leverage vendors to accelerate capabilities, and how to engage clinicians to ensure buy-in. We will explore the keys to success for these elements in the final post of this series.