Changing Marketplace and Societal Dynamics

How Product Makers Can Fight the Gray Market

Ever more consumer goods are being sold cheaply in countries they were not intended for, as shoppers and companies take advantage of price differentials between markets. This “gray market” has been particularly prominent in durable goods, such as apparel, consumer electronics, and toys: It is easy to compare their prices, they have no expiry dates, and they are often expensive enough to make transshipment financially viable.

But it has not stopped there. The phenomenon has spread to fast-moving consumer goods. For example, about 350,000 tons of infant milk formula are parallel-imported each year from Australia to China, where some brands cost four times as much. And at times, all the Coca-Cola Zero sold in Switzerland has been imported from Poland, Serbia, or Ukraine, countries where it can retail at half the Swiss price.

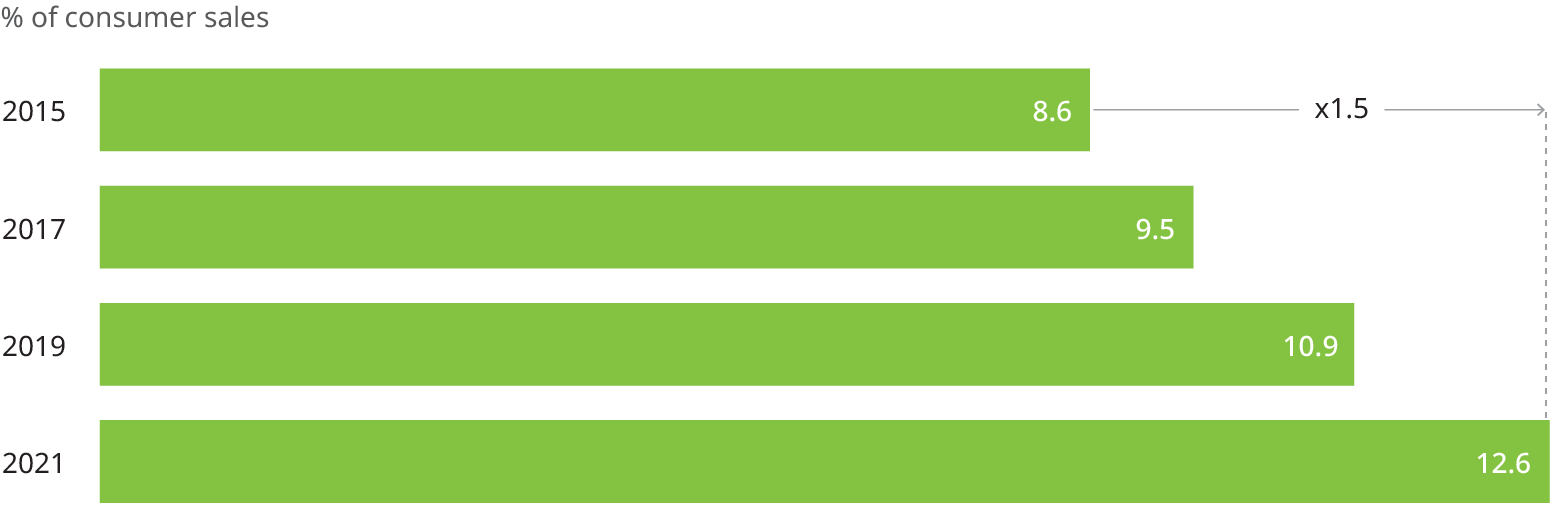

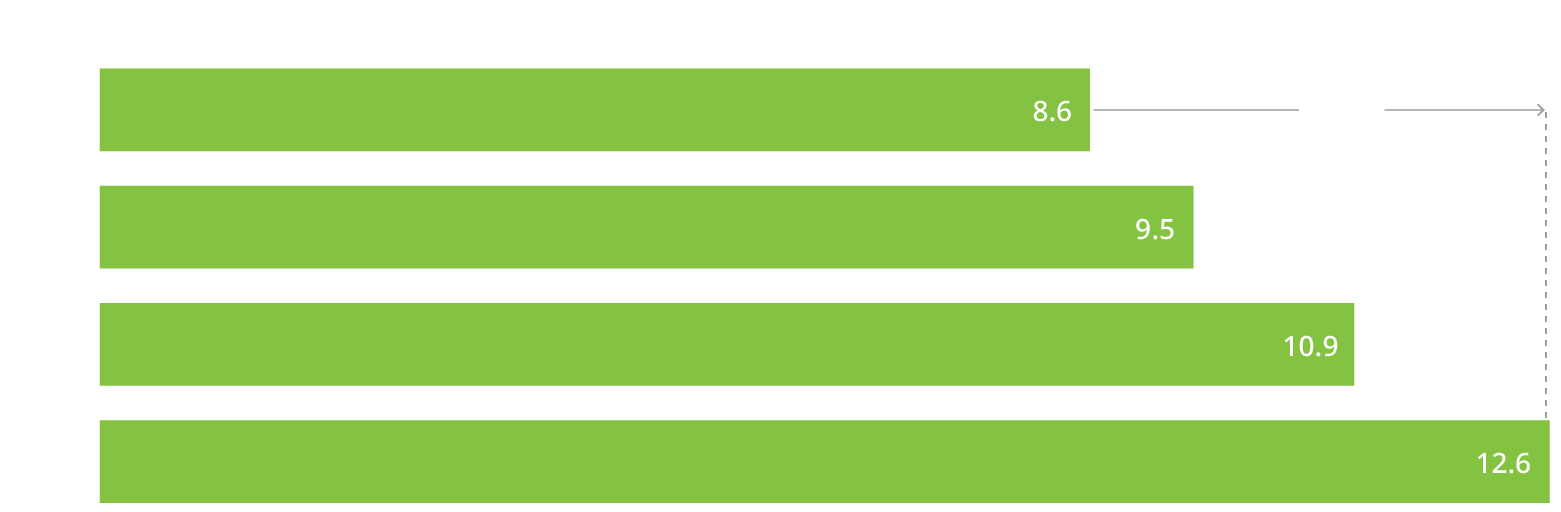

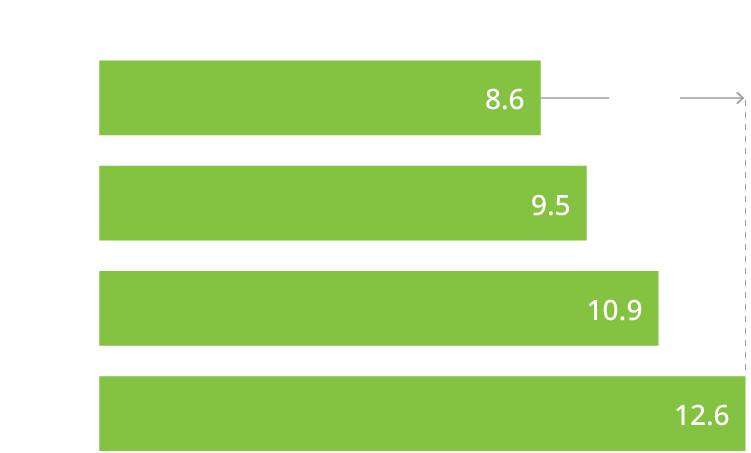

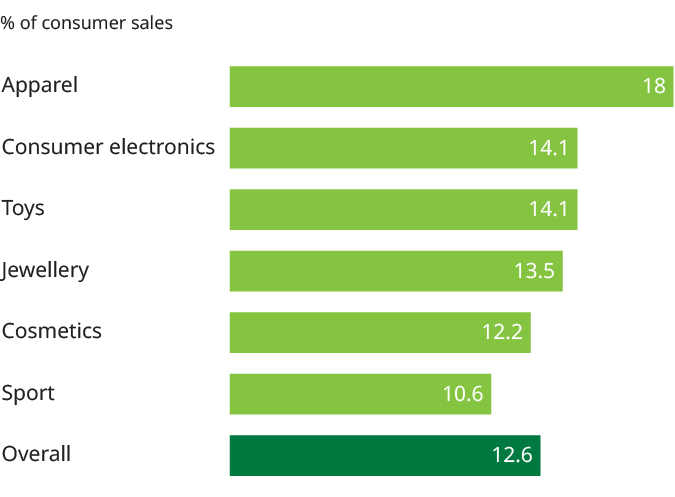

The gray market for consumer goods has expanded by more than 60% in revenues over the last six years, according to Oliver Wyman research. In 2021, 13% of global consumer sales came from products the manufacturer, typically at prices around 20% or 30% below retailers’ net purchasing price for those markets. That shaved around 3 percentage points off consumer goods companies’ gross margins. In addition, the manufacturers had to compensate resellers not participating in the gray market activities for the resulting margin loss due to price erosion in those markets — another 2 percentage points of gross margins. Longer term, a brand becomes perceived as a “bargain brand,” and its value diminishes. (See Exhibit 1).

About 350,000 tons of infant milk formula is sold on the Chinese gray market each year.

However, examples of best practice indicate that the right approach can reduce gray-market volumes significantly — to under 5% for premium firms that carry out strict commercial management and under 10% for mass market firms aiming to raise sell-out volumes.

Exhibit 1: Revenue generated by products that have been sold in countries which they were not meant to be, World

Source: Oliver Wyman analysis

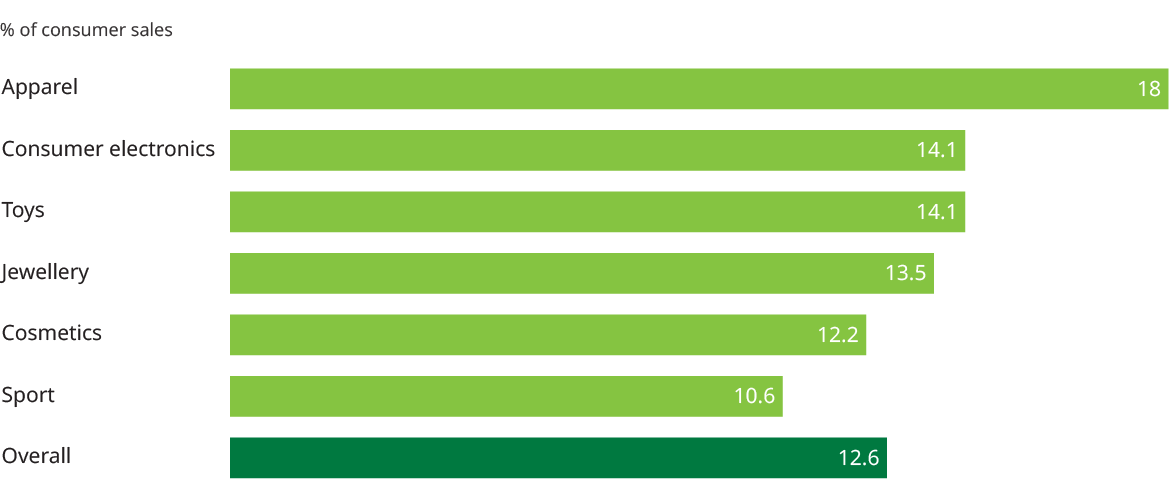

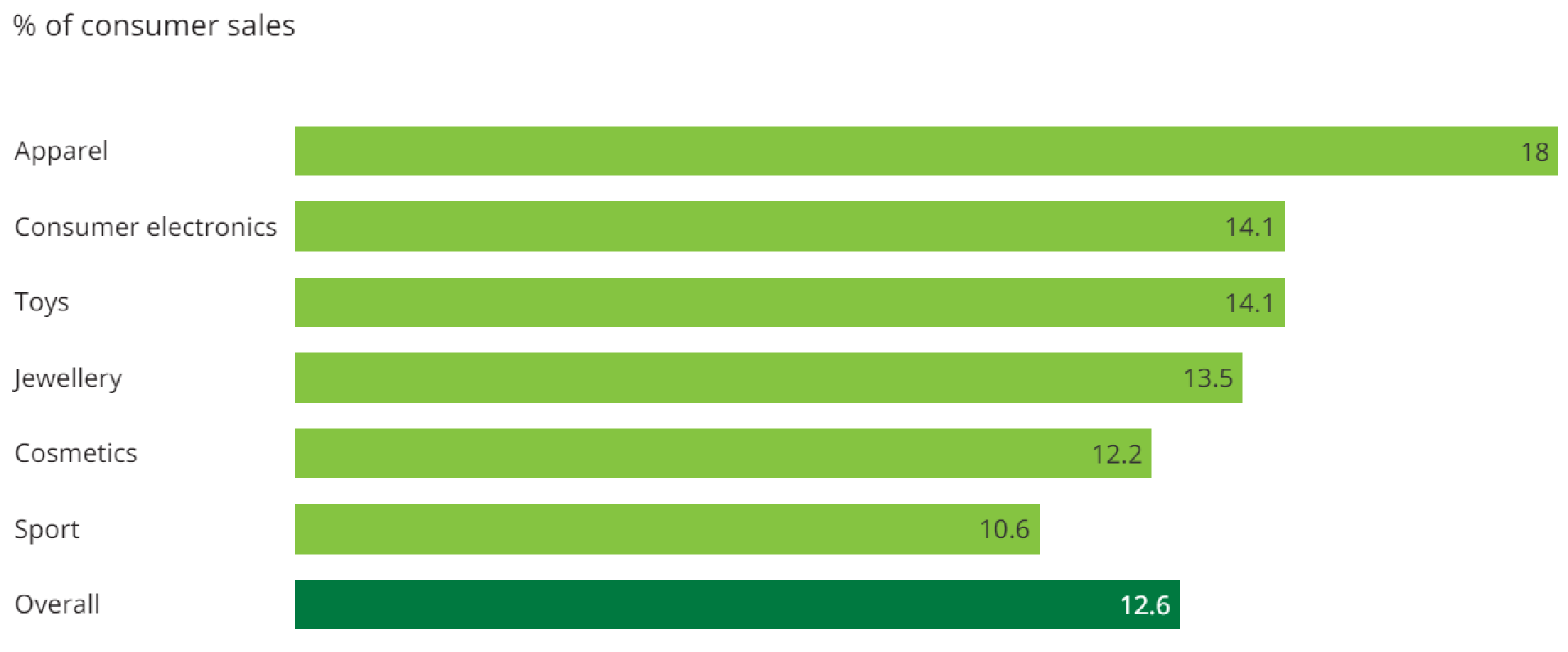

New Shopping Events, New Shopping Channels

One trigger for the gray market has been shopping events, such as China’s November 11 Singles Day and its 618 Shopping Festival — the first 18 days in June. Brands offer resellers low prices to make the most of these opportunities, but some resellers buy more items than they need for the events and then sell the rest in other markets at below-standard prices. Another factor is cross-country procurement by global resellers such as Amazon, which identify the cheapest source for a product and use this to supply a whole region. Smaller players are doing this through international purchasing alliances. Adding to the trend, dedicated gray-market firms have emerged, which buy products in the country where they are cheapest. They then sell them either in bulk to other retailers, directly to end-consumers via their own sites, or through marketplaces. (See Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Revenue generated by products that have been sold in countries which they were not meant to be, World

Source: Oliver Wyman analysis

Once these products appear in a new market at below-market prices, a downwards spiral sets in, as marketplaces and resellers follow the prices of the cheapest retailer. Unhappy trade partners then either reduce their exposure to the products or pressure manufacturers to compensate their margin losses. And manufacturers are forced to mark down prices in their growing direct-to-consumer (D2C) activities. On the side of the consumer, once awareness of the actual, higher price rises, willingness to pay full price for the brands’ products declines. Consequently, brand equity suffers.

We suggest an approach at three levels to fight the gray market: prevent, control, and react.

Prevent. Contracts can stipulate that products only be sold in particular markets and define punishments for infractions. Companies can also forecast each reseller’s demand and allocate volume accordingly, especially for promotions, thus avoiding overdistribution.

Another approach is tight terms and conditions. Instead of offering a product to a reseller at a steep discount to the recommended retail price, a manufacturer can offer just a narrow discount — but add further financial benefits later for resellers that invest in the joint relationship, for example, by optimizing the presentation of the brand. Connecting financial benefits to reseller investments prevents sellers from simply investing margin in low market prices. In addition, recommended-retail and sell-in prices can be harmonized — between different markets in the same region and, as far as possible, between markets in different regions.

In addition, a manufacturer can make the physical products harder to sell outside specific markets. This measure need not be costly — for example, presenting packaging and manuals (where relevant) only in certain languages. Value-added services such as warranties can be designed to apply exclusively to certain markets.

The manufacturer should establish a dedicated team of experts who are close to the markets.

Control. The manufacturer should establish a dedicated team of experts who are close to the markets. They should have sufficient funds to identify and map gray-market activity, for example, by tracking product registrations to check for discrepancies between where a product was sold and where it should have been sold. The team can also make control buys of products that look surprisingly cheap, checking the code on the delivered product to see whether it should have been sold in a different region. Once problems have been identified, the team should analyze the cause of the violations and assess the financial impact.

React. Prevention and control measures must be accompanied by regular action. When a reseller is selling goods bought from the manufacturer on the gray market, the product maker should, in the first instance, send warning letters. The next step is to claim compensation for the sales. If this does not work, then the manufacturer might choose to end the business relationship. When a retailer is selling goods purchased on the gray market, the manufacturer can first ask for offers to be removed and then send official warning letters, where possible. If necessary, legal proceedings can be initiated.

These new forms of action require internal changes, such as training programs for staff. In addition, the company should ensure that financial benefits do not incentivize the gray market. For example, it could subtract the volume being diverted to the gray market from the originating country’s sales targets and add it to those of the teams in regions into which gray-market products are being imported.

Time to Act

Luxury and jewelry firms, which depend on high prices and an upmarket brand image, have been relatively quick to act. However, only 15-36% of surveyed CPG CEOs claim that they are well prepared, while all others are either at the beginning of their journey to fight the gray market or have not started at all. Some do not yet measure the financial damage that results, so are unconvinced of the need to fight it. Others fear that limiting volumes to retailers — to reduce the amount they can distribute through the gray market — could damage their relationships with sizeable retail partners. The above steps have the potential to yield concrete results — for near-term profitability and for the long-term value of a brand.